There is general agreement that a widow must wait a period of time after the death of her husband before re-marrying, to ensure that should she see signs of pregnancy soon after the death of her first husband, the paternity of the child will not be in doubt. The Talmud assumes that all pregnancies become obvious within three months of conception, and so a woman can remarry after she waits three months from the death of her first husband. Shmuel explains the importance of uncontested paternity:

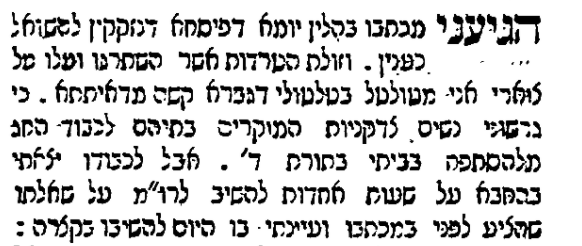

יבמות מד, א

אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל, מִשּׁוּם דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״לִהְיוֹת לְךָ לֵאלֹהִים וּלְזַרְעֲךָ אַחֲרֶיךָ״, לְהַבְחִין בֵּין זַרְעוֹ שֶׁל רִאשׁוֹן לְזַרְעוֹ שֶׁל שֵׁנִי

The verse states with regard to Abraham: “To be a God to you and your seed after you” (Genesis 17:7), which indicates that the Divine Presence rests with someone only when his seed can be identified as being descended from him, i.e., there are no uncertainties with regard to their lineage. Therefore, to prevent any uncertainties concerning the lineage of her child, the woman must wait so that it will be possible to distinguish between the seed of the first husband and the seed of the second husband. After three months, if she has conceived from her previous husband, the pregnancy will already be noticeable.

So far so good. But then the Talmud analyses the viability of a child born prematurely in which the father may be either the first husband who subsequently died, or a second man, to whom the mother re-married very son after the death of her first husband. The Talmud suggests that the women need wait two and a half months after the death of her first husband. If a child is born seven months later, it must have been fathered by the second husband, since (i) if it was fathered by the first husband the gestational period would be nine and a half months, which is assumed to be impossible, and (ii) if it was fathered by the first husband but was born prematurely, the gestational period would have to have been eight months - and as Rashi explains - an eight month fetus is not viable.

“בר תמניא לא חיי Yevamot 42~...an eight month fetus cannot survive”

Elsewhere, the Talmud specifically notes that an eight month fetus is not viable. In Bava Basra, a child born after eight months is declared to be mukzteh, that is, it is in a category of objects that must not be moved on Shabbat:

דתניא בן שמנה הרי הוא כאבן ואסור לטלטלו בשבת

For it was taught in a Braisa. A baby born at eight months of gestation is treated like a stone [on Shabbat, because it is muktzeh.]

The premature baby is given the status of a stone because it was not considered to be viable. As a result, even though all the rules of Shabbat may usually be ignored in order to save a life, in this instance, there is no such provision. The baby will die regardless, so the usual Shabbat rules cannot be violated.

but what about the facts?

But what happens when this rabbinic belief ran up against the facts? Which is to say, how could the rabbis explain the cases in which a woman gave birth to an eight-month fetus, and it did indeed survive? There were surely many examples of this kind of premature birth. How did the rabbis square it with their understanding of things?

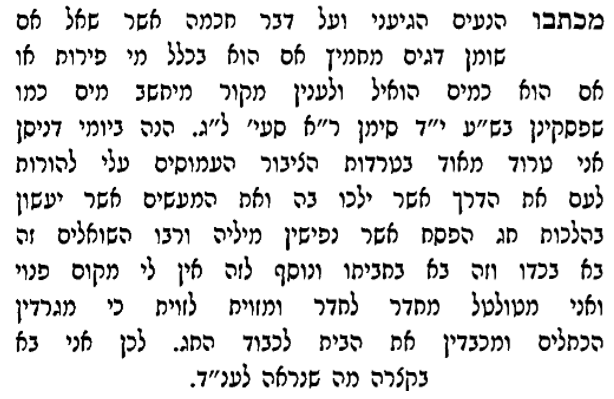

To answer this we turn to the parallel text in the Talmud Yerushalmi (Yevamot 4:2:5). In explaining why the word וַיִיצֶר - “he created” (Gen. 2:7) is written with two yods instead of the expected spelling “וַיִצֶר”, Rabbi Zeira explained (in the name of Rav Huna) that the verse teaches that there are two kinds of gestations:

מְנַיִין שְׁתֵּי יְצִירוֹת. רִבִי זְעִירָא בְשֵׁם רִבִּי הוּנָא. וַיִיצֶר. יְצִירָה לְשִׁבְעָה וִיצִירָה לְתִשְׁעָה. נוֹצָר לְשִׁבְעָה וְנוֹלָד לִשְׁמוֹנָה חַיי. כָּל־שֶׁכֵּן לְתִשְׁעָה. נוֹצָר לְתִשְׁעָה וְנוֹלָד לִשְׁמוֹנָה אֵינוֹ חַייָה. נוֹצָר לְתִשְׁעָה וְנוֹלָד לְשִׁבְעָה

From where the two creations? Rebbi Ze‘ira in the name of Rebbi Huna: “He created”, a creation for seven and a creation for eight. If he was created for seven but born at eight, he lives; so much more if [born] by nine. If he was created for nine and born at eight, he does not live.

Did you follow that? There are really two kinds of fetus, one that will be viable at seven months and another at nine. If a seven month fetus is born at eight months, it can live, because it was really a fully formed seven month fetus. But if a nine month fetus is born after only eight months, it will not survive, because it was never fully formed. In this way, Rabbi Huna was able to explain the observation that there are in fact some babies born after eight months that are viable. It’s clever. But hardly persuasive. Rather than abandon the whole eight-month-fetus-is-not-viable thing, Rabbi Huna came up with a new theory , and even found a source for it in the Torah itself.

This belief - that a fetus of seven months gestation may survive, but one born in the eighth month of gestation cannot do so - is very odd. But it wasn't a uniquely Jewish belief.

“...it is the women who make the judgments and ... insist that the eighth-month babies do not survive, but the others do. ”

The Eight Month Fetus in the Ancient World

Homer's Iliad, written around the 8th century BCE, records that a seven month fetus could survive. But it is not until Hippocrates (c. 460-370 BCE, or some 500 years before Shmuel), that we find a record of the belief that a fetus of eight months' gestation cannot survive, while a seventh month fetus (and certainly one of nine month gestation) can. His Peri Eptamenou (On the Seventh Month Embryo) and Peri Oktamenou (On the Eight-Month Embryo) date from the end of the fifth century BCE, but this belief is viewed with skepticism by Aristotle.

In Egypt, and in some other places where the women are fruitful and are wont to bear and bring forth many children without difficulty, and where the children when born are capable of living even if they be born subject to deformity, in these places the eight-months' children live and are brought up, but in Greece it is only a few of them that survive while most perish. And this being the general experience, when such a child does happen to survive the mother is apt to think that it was not an eight months' child after all, but that she had conceived at an earlier period without being aware of it.

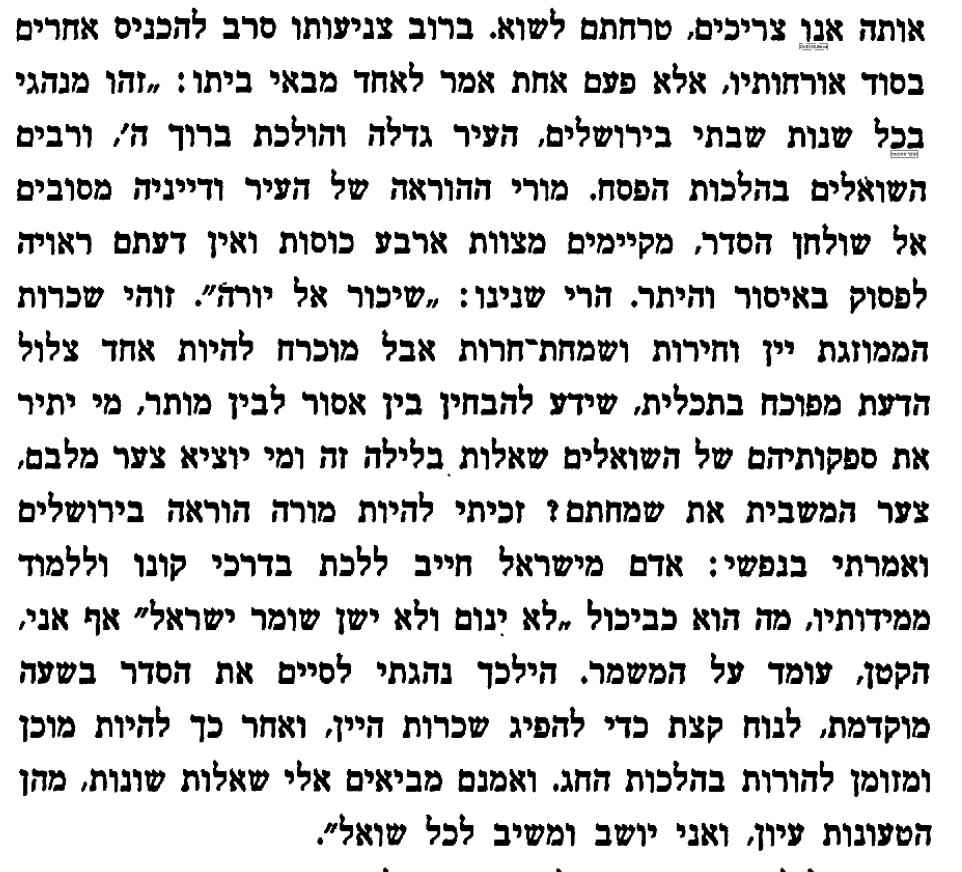

The belief that an eight month fetus cannot survive has a halakhic reification: Maimonides ruled that if a boy was born prematurely in the eighth month of his gestation and the day of his circumcision (8 days after his birth) fell out on shabbat, the circumcision - which otherwise would indeed occur on shabbat, is postponed until Sunday, the ninth day after his birth.

ומי שנולד בחדש השמיני לעבורו קודם שתגמר ברייתו שהוא כנפל מפני שאינו חי... אין דוחין השבת אלא נימולין באחד בשבת שהוא יום תשיעי שלהן

(הלכות מילה 1:11)

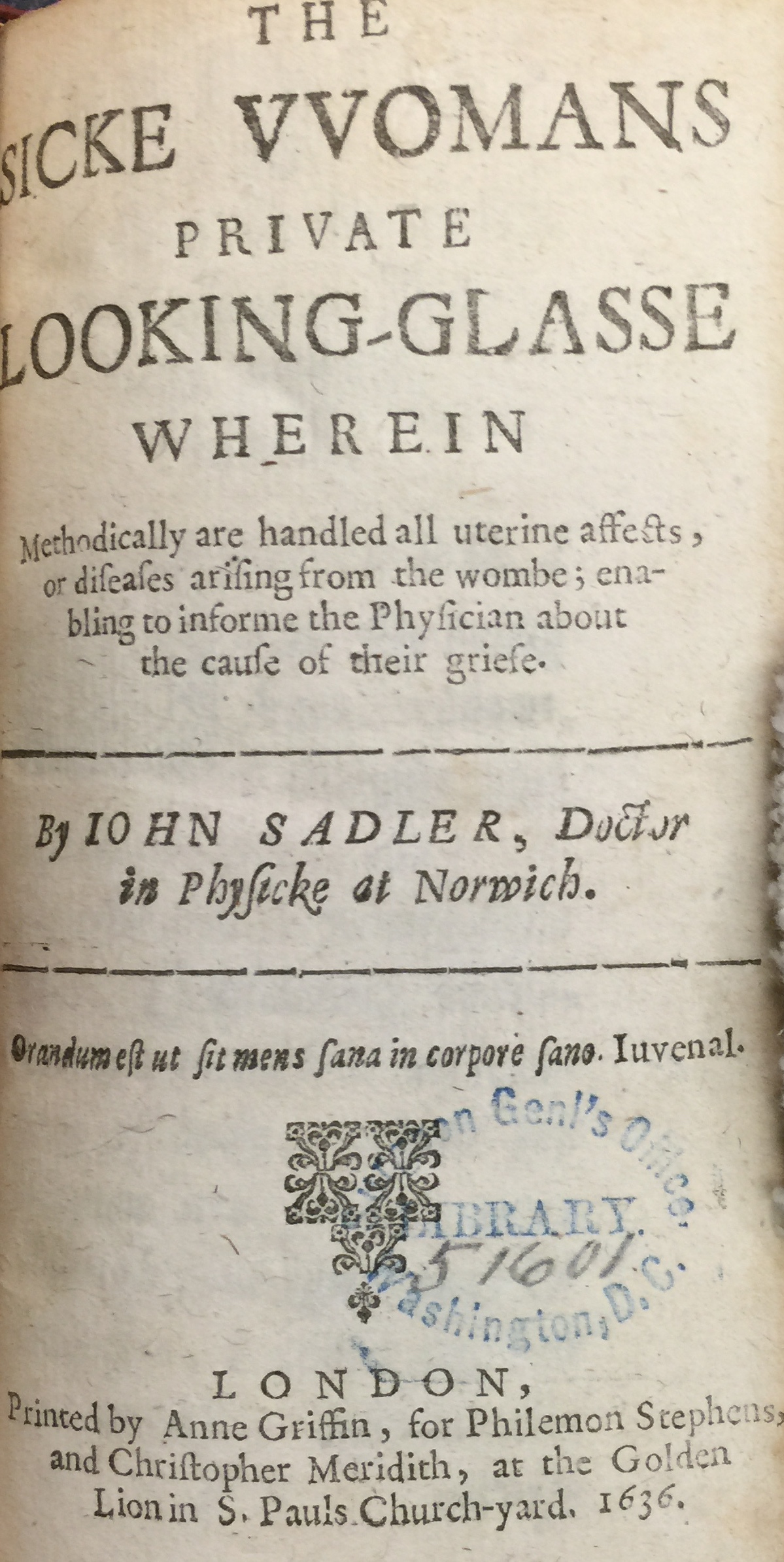

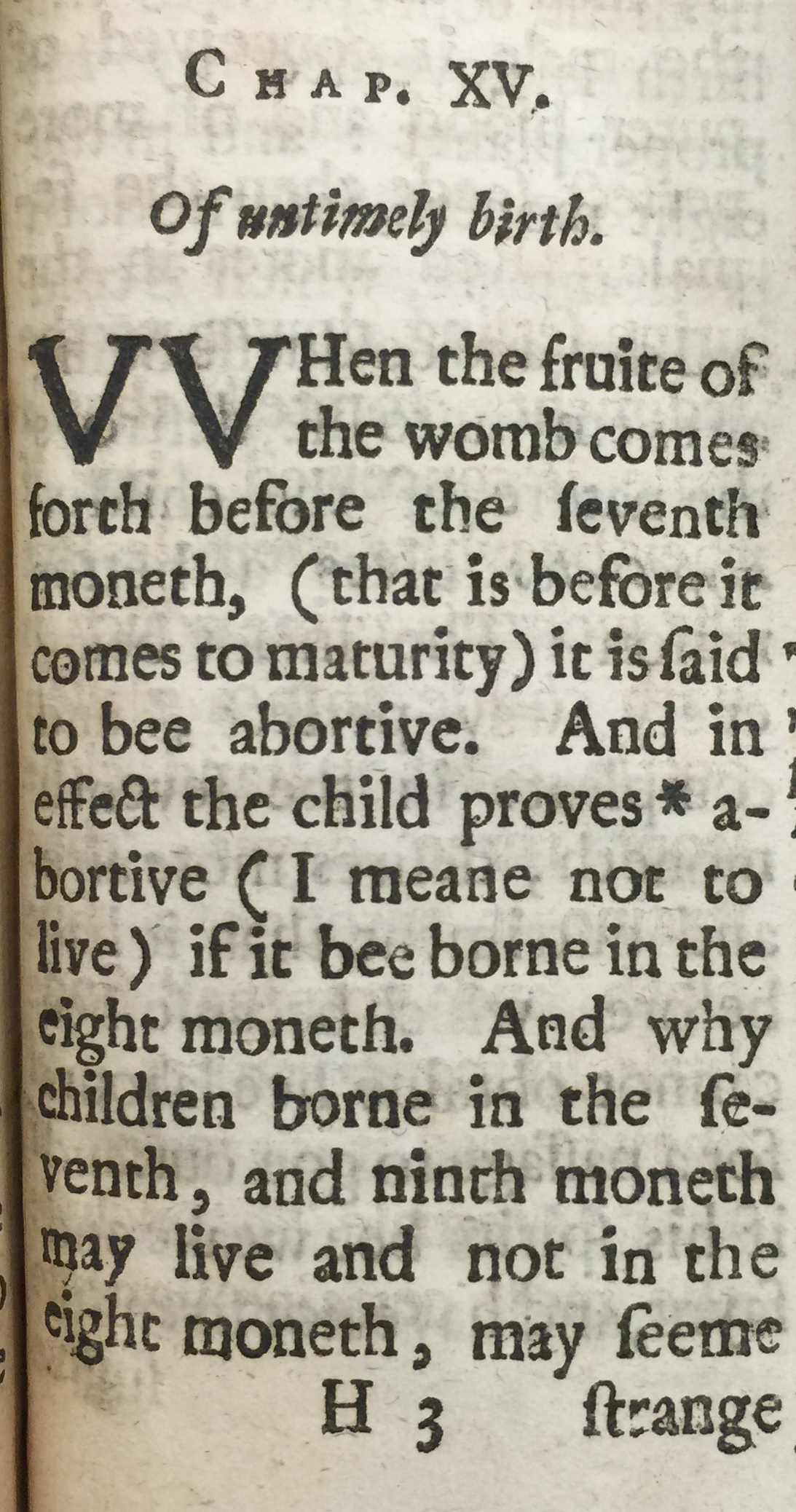

This belief persisted well into the early modern era. Here is a state of the art medical text published in 1636 by John Sadler. Read what he has to say on the reasons that an eight month fetus cannot survive (and note the name of the publisher at the bottom of the title page-surely somewhat of a rarity then) :

Saturn predominates in the eighth month of pregnancy, and since that planet is "cold and dry"," it destroys the nature of the childe". That, or some odd yearning of the child to be born in the seventh but not the eight month (according to Hippocrates) is the reason that a child born at seven and nine months' gestation may survive, but not one born at after only eight months.

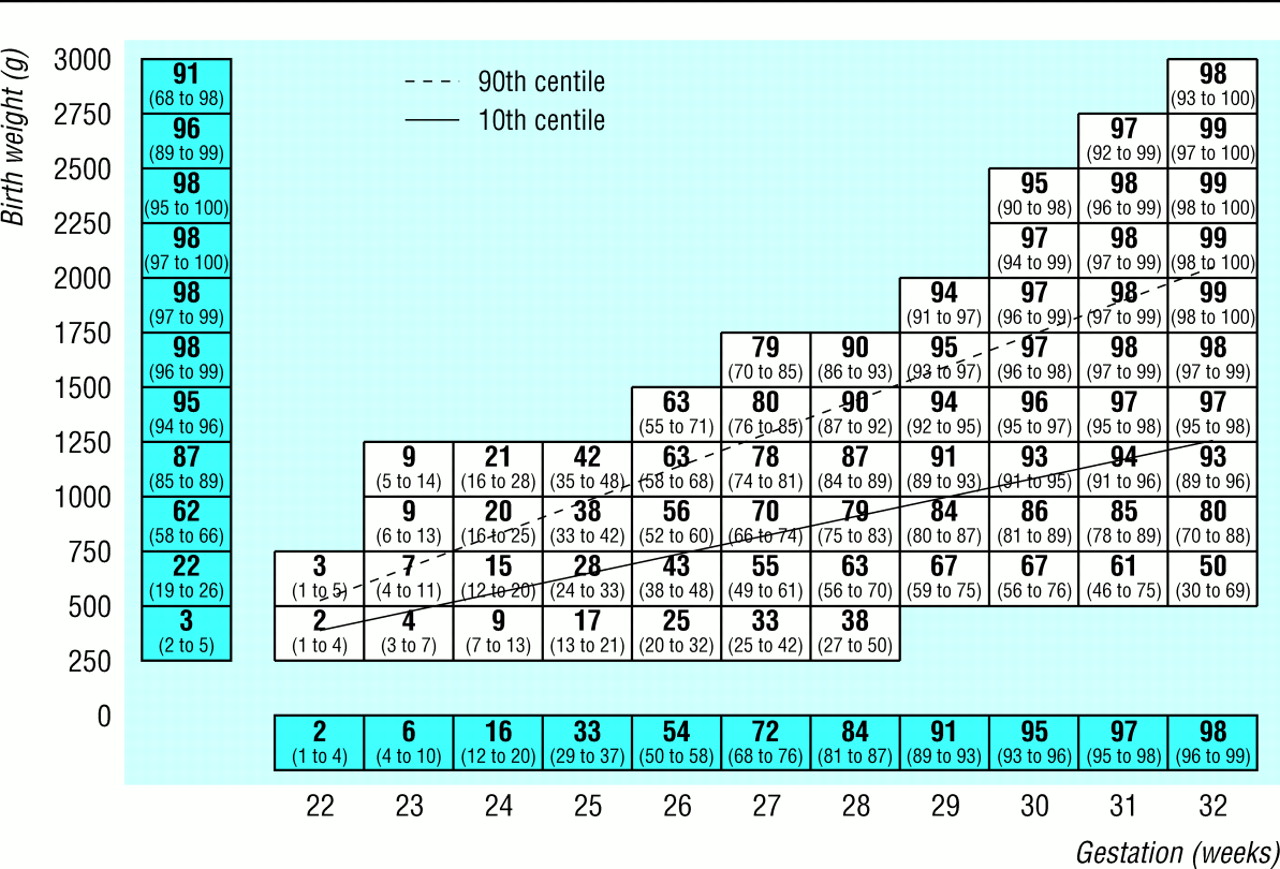

Today, gestational length is of course critical, and, all things being equal, the closer the gestational length is to full term, the greater the likelihood of survival. We can say with great certainty, that an infant born at 32 weeks or later (that's about eight months) is in fact more likely to survive than one born at 28 weeks (a seven month gestation.) In fact, a seven month fetus has a survival rate of 38-90% (depending on its birthweight), while an eight month fetus has a survival rate of 50-98%. Here is the data, taken from a British study.

Draper Elizabeth S, Manktelow Bradley, Field David J, James David. Prediction of survival for preterm births by weight and gestational age: retrospective population based study BMJ 1999; 319:1093

More recently, a study from the Technion in Haifa showed that even the last six weeks of pregnancy play a critical role in the development of the fetus. This study found a threefold increase in the infant death rate in those born between 34 and 37 weeks when compared full term babies.

You can read more on the history of the eight month fetus in a 1988 paper by Rosemary Reiss and Avner Ash. From what we have reviewed, the talmudic belief in the unusually low survival rate of an eight month fetus (compared to a seven month one) is one that was widely shared in the ancient world. And one that is not supported by any of the evidence we now have.

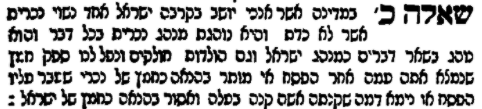

Pregnancy as a contraceptive

We now turn to the second pregnancy related topic on today’s daf. According to the Talmud, if a mother becomes pregnant while nursing, her milk supply will become turbid and (unless an alternative is found) her nursing child may die.

יבמות מד, ב

סתם מעוברת למניקה קיימא דלמא איעברה ומעכר חלבה וקטלה ליה

Many of us will have heard that it is not possible for a mother to become pregnant while she is breast-feeding, and many mothering websites address this question. So how can the Talmud suggest that a breast-feeding mother can conceive?

“You may have heard from a friend that nursing can serve as a form of birth control — and while that’s not entirely untrue, it’s not the whole story either.”

The question we have to answer is, how good a contraceptive is nursing? In a word (well, actually two words) it depends. In the first 3-6 months after birth, and if the baby is fed only on breast milk, some claim that breast feeding is a pretty good contraceptive, and is effective about 98% of time. But if mum skips a feed here or there, or if mum's periods have restarted, all bets are off. Here's data from an old paper on the topic. Take a close look at the last column- the failure rates per 100 women.

Those are high failure rates -as high as one in five - which makes it a pretty unreliable contraceptive. A review of breastfeeding as a contraceptive was published in 2003 in the widely respected Cochrane Reviews; it concluded that "[f]ully breastfeeding women who remain amenorrheic have a very small risk of becoming pregnant in the first 6 months after delivery when relying on lactational sub fertility". However, - and this is really important - it is not possible to know when amenorrhea is likely to end, and so an IUD is suggested as additional contraception wherever possible.

Overall, the talmudic suggestion that conception is possible while a mother is breastfeeding her child is, scientifically speaking, spot on.