About forty years ago, while a medical student in London, I had the good fortune of visiting the Valmadonna Trust Library, then the finest private library of Hebrew books in the world. (How I got there is another story for another time). And while there, I held the Talmud that once belonged to Westminster Abbey. It also may been owned by Henry VIII, who had brought it from Venice in order to help him end his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the first of his many wives. The story of Henry VIII's purchase of the Bomberg Talmud - the first complete printed Talmud - actually hinges on Yevamot, and whether the rules of levirate marriage, or yibum, applied to him.

Henry VIII performed Yibbum

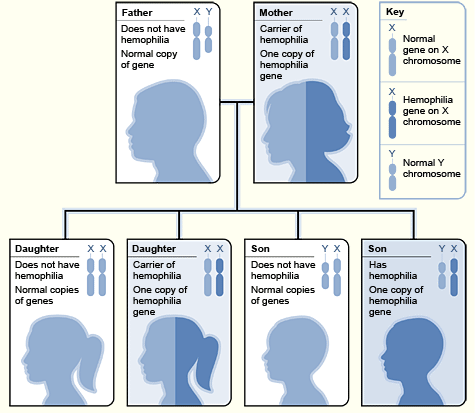

Catherine of Aragon was actually a widow, having first been married to Henry's older brother Arthur. About six months after Catherine married Arthur he died childless, and in 1509 his younger brother Prince Henry married his widow. (Is this beginning to sound familiar?) One more thing to know: Catherine claimed that her marriage to Arthur had never been consummated; this is important later in the story. (And here is an interesting historic footnote: it was Catherine's parents, Ferdinand and Isabella who had expelled the Jews from Spain.)

Fast forward to 1525. Henry is now King Henry VIII, and has had one daughter with Catherine. He wanted a son, and now wished to marry Ann Boleyn, but what was he to do with Catherine, his existing wife? Divorce, remember, was tricky for this Catholic King. And here is where the Talmud comes in.

Henry argued that his marriage to Catherine should be dissolved since it was biblically forbidden for a man to marry his sister-in-law. (Henry claimed years earlier that he could marry her because the marriage to his brother had not been consummated. See, I told you that was important information...)

“Turpitudinem uxoris fratris tui non revelavit

עֶרְוַ֥ת אֵֽשֶׁת־אָחִ֖יךָ לֹ֣א תְגַלֵּ֑ה עֶרְוַ֥ת אָחִ֖יךָ הִֽוא ”

But as we all know from the last several weeks of study, the Bible commands a man to marry his widowed sister-in-law if his brother died without children. Since Arthur died childless, it could be argued that Henry was now fulfilling the biblical requirement of levirate marriage - known as yibum.

“quando habitaverint fratres simul et unus ex eis absque liberis mortuus fuerit uxor defuncti non nubet alteri sed accipiet eam frater eius et suscitabit semen fratris sui

כִּֽי־יֵשְׁב֨וּ אַחִ֜ים יַחְדָּ֗ו וּמֵ֨ת אַחַ֤ד מֵהֶם֙ וּבֵ֣ן אֵֽין־ל֔וֹ לֹֽא־תִהְיֶ֧ה אֵֽשֶׁת־הַמֵּ֛ת הַח֖וּצָה לְאִ֣ישׁ זָ֑ר יְבָמָהּ֙ יָבֹ֣א עָלֶ֔יהָ וּלְקָחָ֥הּ ל֛וֹ לְאִשָּׁ֖ה וְיִבְּמָֽהּ ”

How was this conundrum to be resolved? Let's have the late great Jack Lunzer, the custodian of the library, tell the story. (You can also see the video here. Sorry about the ads. They are beyond our control.)

Adapted from Dailymotion.com

As Lunzer tells us, the Talmud was obtained from Venice to help King Henry VIII find a way to divorce his wife (and former sister-in-law) Catherine, and so be free to marry Ann Boleyn. In fact, it's a little bit more complicated than that. Behind the scenes were Christian scholars who struggled to reconcile the injunction against a man marrying his sister-in-law, with the command to do so under specific circumstances. In fact the legality of Henry's marriage had been in doubt for many years, which is why Henry had obtained the Pope's special permission to marry.

John Stokesley, who later became Bishop of London, argued that the Pope had no authority to override the word of God that forbade a man from marrying his brother's wife. As a result the dispensation the Pope had given was meaningless, and Henry's marriage was null and void. In this way, Henry was free to marry. But what did Stokesley do with the passages in Deuteronomy that require yibum? He differentiated between them. The laws in Leviticus, he claimed, were both the word of God and founded on natural reason. In this way they were moral laws; hence they applied to both Jew and Christian. In contrast, the laws found in Deuteronomy, were judicial laws, which were ordained by God to govern (and punish) the Jews - and the Jews alone. They were never intended to apply to any other people, and so Henry's Christian levirate marriage to Catherine was of no legal standing. There was therefore no impediment for Henry to marry Ann. As you can imagine, this rather pleased the king.

The origins of the Valmadonna Talmud

It is unlikely that the Valmadonna Library Bomberg Talmud was indeed the very same one that Henry had imported from Venice. According to Sotheby's and at least one academic, it actually came from the library of an Oxford professor of Hebrew, who bequeathed it to the Abbey. In any event, the Bomberg Talmud lay undisturbed at Westminster Abbey for the next four hundred years. How Lunzer obtained it for his library is possibly the greatest story in the annals of Jewish book collecting. In the 1950s there was an exhibition in London to commemorate the readmission of the Jews to England under Cromwell. Lunzer noted that one of the books on display, from the collection of Westminster Abbey, was improperly labelled, and was in fact a volume of a Bomberg Talmud. Lunzer called the Abbey the next day, told them of his discovery, and suggested that he send some workers to clean the rest of the undisturbed volumes. They discovered a complete Bomberg Talmud in pristine condition, and Lunzer wanted it. But despite years of negotiations with the Abbey, Lunzer's attempts to buy the Talmud were rebuffed.

“Mr. Lunzer, we at the Abbey consider our Babylonian Talmud to be part of the Abbey itself. ”

Then in April 1980, Lunzer's luck changed. He read in a brief newspaper article that the original 1065 Charter of Westminster Abbey had been purchased by an American at auction, but because of its cultural significance the British Government were refusing to grant an export license. Lunzer called the Abbey, was invited for tea, and a gentleman's agreement was struck. He purchased the Charter from the American, presented it to the Abbey, and at a ceremony in the Jerusalem Chamber of Westminster Abbey the nine volumes of Bomberg's Babylonian Talmud were presented to the Valmadonna Trust. It's a glorious story, and it's so much better when Lunzer himself tells it, as he does here: (You can also see the video here, and end it at 14.35. We continue to apologize for those ads.)

Adapted from Dailymotion.com

In December 2015, the Westminster Abbey Talmud was sold at Sotheby's in New York $9.3 million. The buyer was anonymous, and so, in a flash, the magical Talmud I had once held in my hands moved to a new private collection. I hope the owner enjoys his (or her) new treasure.