One hypothetical too many

Sometimes, the endless talmudic questioning can go too far. If a baby pigeon is found within 50 cubits of a coop, it is presumed to belong to the owner of that coop. If it is found further away than 50 cubits, it belongs to the finder. Ever keen to push the limits of rabbinic law, Rabbi Yirmiyah asked “if one foot of the pigeon is within the fifty cubits and one foot is outside, to whom does it belong?” This apparently was one question too many. The rabbis (rather unfairly in my opinion) expelled Rabbi Yirmiyah from the Yeshivah for asking it.

בבא בתרא כג, ב

בָּעֵי רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה רַגְלוֹ אַחַת בְּתוֹךְ חֲמִשִּׁים אַמָּה וְרַגְלוֹ אַחַת חוּץ מֵחֲמִשִּׁים אַמָּה מַהוּ וְעַל דָּא אַפְּקוּהוּ לְרַבִּי יִרְמְיָה מִבֵּי מִדְרְשָׁא

Rabbi Yirmeya raises a dilemma: If one leg of the chick was within fifty cubits of the dovecote, and one legwas beyond fifty cubits, what is the halakha? The Gemara comments: And it was for his question about this far-fetched scenario that they removed Rabbi Yirmeya from the study hall, as he was apparently wasting the Sages’ time.

Tomorrow’s bizarre case is one of many that we encounter as we make our way through the Babylonian Talmud. Consider this whopper, that we learned at the end of last year:

בבא קמא כז, א

אָמַר רַבָּה: נָפַל מִן הַגָּג וְנִתְקַע — חַיָּיב בְּאַרְבָּעָה דְּבָרִים, וּבִיבִמְתּוֹ לֹא קָנָה. בְּנֵזֶק, בְּצַעַר, בְּשֶׁבֶת, בְּרִפּוּי. אֲבָל בּוֹשֶׁת לָא מִיחַיַּיב, דְּאָמַר מָר: אֵין חַיָּיב עַל הַבּוֹשֶׁת עַד שֶׁיִּתְכַּוֵּון

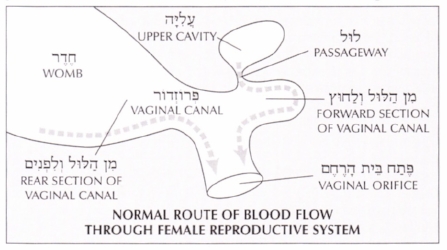

Rabba said: One who fell from a roof and was inserted into a woman due to the force of his fall is liable to pay four of the five types of indemnity that must be paid by one who damaged another, and if she is his yevama he has not acquired her in this manner. He is liable to pay for injury, pain, loss of livelihood, and medical costs. However, he is not liable to pay for the shame he caused her, as the Master said: One is not liable to pay for shame unless he intends to humiliate his victim…

As weird Talmudic cases go, this is among the weirdest. It is entirely impossible, and not least because this would happen. Did the rabbis of the Talmud really believe that such a case could occur? To answer this, let’s consider come other rather implausible cases from across the Babylonian Talmud.

The AMAZING Shechita Knife

We begin with a fanciful question that is somewhat analogous to falling intercourse case. What happens if a person throws a knife across the room, but in doing so the flying knife somehow manages to cut the neck of an animal in just the correct fashion to perform a kosher shechita (ritual slaughter). Is the meat of this slaughtered animal kosher?

חולין לא, א

דתני אושעיא זעירא דמן חבריא זרק סכין לנועצה בכותל והלכה ושחטה כדרכה ר' נתן מכשיר וחכמים פוסלים הוא תני לה והוא אמר לה הלכה כר' נתן

Oshaya, the youngest of the company of Sages, taught a baraita: If one threw a knife to embed it in the wall and in the course of its flight the knife went and slaughtered an animal in its proper manner, Rabbi Natan deems the slaughter valid and the Rabbis deem the slaughter not valid. Oshaya teaches the baraita and he says about it: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Natan that there is no need for intent to perform a valid act of slaughter.

The Fish That Pulled a Plough

The Bible (Deuteronomy 22:10) forbids a farmer to plough his land using an ox and a donkey together. While no reason for this law is given, we might suppose it has something to do with the concern that doing so might cause unnecessary pain to the smaller (or perhaps the larger?) animal. Regardless of the reason, later in our tractate the Talmud explains that this law applies to any kind of work and any two different species of animal. Then comes this fantastic question: “What is the law if someone pulls his wagon using a goat and a fish?”

בבא קמא נה, א

בעי רחבה המנהיג בעיזא ושיבוטא מהו מי אמרינן כיון דעיזא לא נחית בים ושיבוטא לא סליק ליבשה לא כלום עביד או דלמא השתא מיהת קא מנהיג

The Sage Rachava raised a dilemma: With regard to one who drives a wagon on the seashore with a goat and a shibbuta, a certain species of fish, together, pulled by the goat on land and the fish at sea, what is the halakha? Has he violated the prohibition against performing labor with diverse kinds, in the same way that one does when plowing with an ox and a donkey together, or not?

This turned out to be such a hard question that the Talmud could not answer it. The Rosh concludes though that just to be sure, best not to hitch up your wagon to a fish, if you also intend for it to be pulled by a goat (ולא איפשיטא ואזלינן לחומרא). Don’t say you weren’t warned.

The Bird that built her nest on a person’s head

The Bible also demands that the mother bird must be shooed away before collecting the eggs upon which she is brooding. But what happens if a bird makes her nest in a person’s hair? Must this mother be driven away before her eggs are collected? (Chullin 139b)

חולין קלט, ב

אמרי ליה פפונאי לרב מתנה מצא קן בראשו של אדם מהו? אמר (שמואל ב טו, לב) ואדמה על ראשו

The residents of Pappunya said to Rav Mattana: If one found a nest on the head of a person, what is the halakha with regard to the mitzva of sending away the mother? Is the nest considered to be on the ground, such that one is obligated in the mitzva? Rav Mattana said to them that one is obligated in the mitzva in such a case because the verse states: “And earth upon his head” (II Samuel 15:32), rather than: Dirt upon his head, indicating that one’s head is considered like the ground.

(And just to be clear - the Talmud is not discussing a case like this one, in which a woman allowed an abandoned fledgling to nest in her long har for 84 days, though it is, I will admit, a very touching story.)

The Role of Bizarre cases

In a 2004 paper published in Thalia: Studies in Literary Humor, Hershey Friedman, a Professor of Business at Brooklyn College, suggested that “whether a situation is possible or not is immaterial when the Talmud is trying to establish legal principles.”

Purely theoretical (at least in their days) cases are discussed because the sages felt that principles derived from these discussions would clarify the law and thus provide a more thorough understanding of it. Discussions of theoretical cases in the Talmud have allowed scholars of today to use the Talmudic logic and principles to solve current legal questions

The theoretical questions make a legal point, and it is that legal point that is the real object of the discussion. Whether or not the case could actually happen is immaterial. Friedman also suggests that these unusual cases serve to keep the material interesting, and also act as brain teasers, which don’t necessarily make a legal point but serve to sharpen the minds of both the students and the teachers who ask them.