The Origins of the Keri-Ketiv

Summarizing the scholarship, Emanuel Tov suggested four possible origins of the kri-ketiv:

They are corrections

They are variant spellings

They are marginal corrections that later became variant spellings

They are reading traditions

Most scholars adhere to the third reason. “If that view is correct,” he wrote, “most of the Ketib-Qere interchanges should be understood as an ancient collection of variants. Indeed, for many categories of Ketib-Qere interchanges similar differences are known between ancient witnesses [i.e. very old manuscripts].

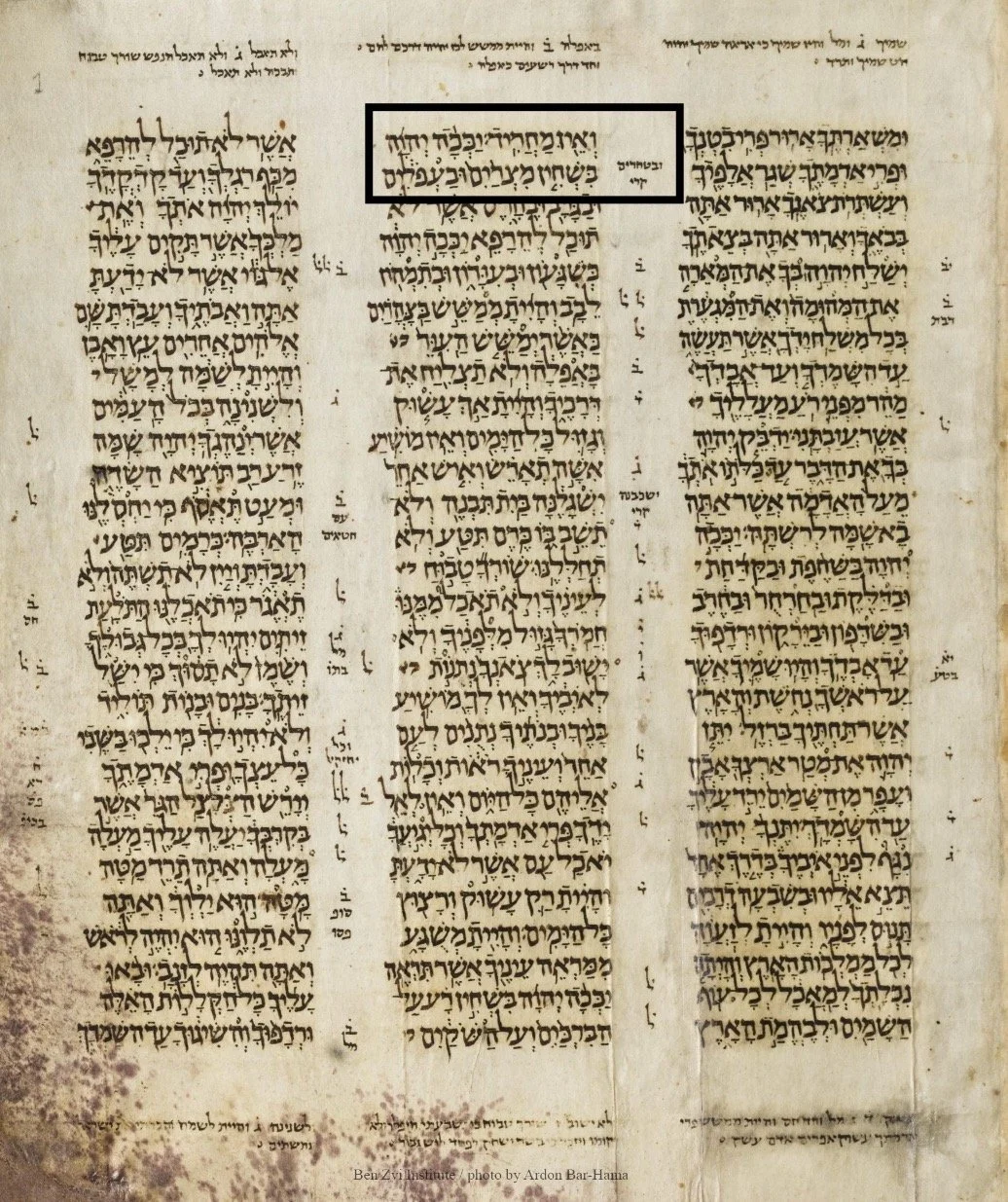

Sometimes the keri-ketiv avoids profanation, such as the perpetual reading of God’s four-letter name as Adonai. And sometimes they serve “as the replacement of possibly offensive words with euphemistic expressions.” This is what is going on in this week’s parsha, where ובעפלים (and with hemorrhoids) is replaced with וּבַטְּחֹרִים (and with tumors). The Talmud makes this cleaning up of the text explicit:

מגילה כה, ב

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: כל הַמִּקְרָאוֹת הַכְּתוּבִין בַּתּוֹרָה לִגְנַאי — קוֹרִין אוֹתָן לְשֶׁבַח, כְּגוֹן: ״יִשְׁגָּלֶנָּה״ — יִשְׁכָּבֶנָּה, ״בַּעֲפוֹלִים״ — בַּטְּחוֹרִים, ״חִרְיוֹנִים״ — דִּבְיוֹנִים, ״לֶאֱכוֹל אֶת חוֹרֵיהֶם וְלִשְׁתּוֹת אֶת מֵימֵי שִׁינֵּיהֶם״ — לֶאֱכוֹל אֶת צוֹאָתָם וְלִשְׁתּוֹת אֶת מֵימֵי רַגְלֵיהֶם

The Sages taught in a baraita: All of the verses that are written in the Torah in a coarse manner are read in a refined manner. For example, the term “shall lie with her [yishgalena]” (Deuteronomy 28:30) is read as though it said yishkavena, which is a more refined term. The term “with hemorrhoids [bafolim]” (Deuteronomy 28:27) is read bateḥorim. The term “doves’ dung [chiryonim]” (II Kings 6:25) is read divyonim. The phrase “to eat their own excrement [choreihem] and drink their own urine [meimei shineihem]” (II Kings 18:27) is read with more delicate terms: To eat their own excrement [tzo’atam] and drink their own urine [meimei ragleihem].

So that explains why the word ובעפלים is read as וּבַטְּחֹרִים. But why are these kinds of swellings mentioned among the curses that await the Israelites if they fail to heed the word of God? Is that the best punishment that God can come up with? Well, it turns out that ophalim likely referenced a truly awful punishment, one that would instill dread and fear. I am talking about bubonic plague.

More than You ever wanted to know about Biblical Hemorrhoids

Let’s fast forward to the Book of Samuel. Having entered the Promised Land, the people of Israel began a long military campaign against its inhabitants, the foremost of which were the Philistines. But they lost not only their battles, but also their Ark, which had been brought to the battlefield in a last-ditch attempt at victory. The captured Ark was taken to Ashdod and placed in a temple to Dagon. God then directed his anger against the Philistines in a most unusual way. He destroyed the idols in the temple and then “struck Ashdod and its territory with swellings” (I Sam 5:6). When the Ark was moved to Gath, another outbreak of “swellings” followed: “The hand of the Lord came against the city, causing great panic; He struck the people of the city, young and old, so that swellings broke out among them” (I Sam 5:9).”

Having understood the terrible danger of keeping the Ark captive, the Philistines sent it back to Israel, but were counseled by their priests not to “send it away without anything; you must also pay an indemnity to Him.” This reparation took a most unusual form: “five golden swellings and five golden mice” (I Sam 6:4). Just what these swellings were is not clear, but there are two possibilities. The first is they were lymph glands in the groin, swollen from infection from bubonic plague. The second is they were hemorrhoids. Both possibilities are hinted to in the Hebrew text and its many translations.

Plague and Bubos

These two quite distinctive words in our parsha - עפלים and טְּחֹרִים have led to the differing explanations of the epidemic. The identification of the Philistine epidemic as bubonic plague privileges the written text, עפלים ophalim. Bubonic plague got its name from the buboes, which are swellings in the axillae and groin. These are the lymph nodes that swell with bacteria and the body’s own dead cells white cells. Bubonic plague is caused by a bacterium called Yersinia Pestis, which is found in fleas that primarily feed on mice and rats, though they can also leap to humans. It swept through Europe as the Black Death in a series of deadly waves that began around 1347, killing a third of the population. But it was also around long before then; fragments from an ancestor of Yersina Pestis have been detected in samples over 3,000 years old.

The Hebrew Bible doesn’t mention the role of rodents in spreading the epidemic, but the Greek translation known as the Septuagint does. This translation was composed around the third century B.C.E. for the Jews of Alexandria, and it adds a detail not found in the Hebrew original: “And the Ark was seven months in the country of the Philistines, and their land brought forth swarms of mice.” These “swarms of mice,” missing from the Hebrew text, are a key to identifying the epidemic. Rodents play a key role in the transmission of bubonic plague. It was these swarms of mice (or really rats, which are the primary host for the rat flea that carries the plague bacteria Yersinia) that were responsible for spreading the plague among the Philistines, causing the lymphatic swellings that characterize the bubonic plague.

One of the first people to identify the outbreak as bubonic plague was the Swiss naturalist Johan Jakob Scheuchzer, who died in 1733. Scheuchzer’s many works included the four-volume Latin Physica Sacra, where he noted that ophalim were buboes. “I therefore come to the conclusion,” he wrote, “that the disease which cased so many deaths among the Philistines was real plague.” But Sheuchzer’s written works were predated by the artist Nicolas Poussin (1594– 1665), whose painting The Plague of Ashdod became “the most imitated and celebrated plague painting of the seventeenth century.”