On today’s page of Talmud we read that rain on Sukkkot is a bad omen. Continuing along with this theme, the Talmud describes another bad omen: a solar eclipse:

סוכה כט, א

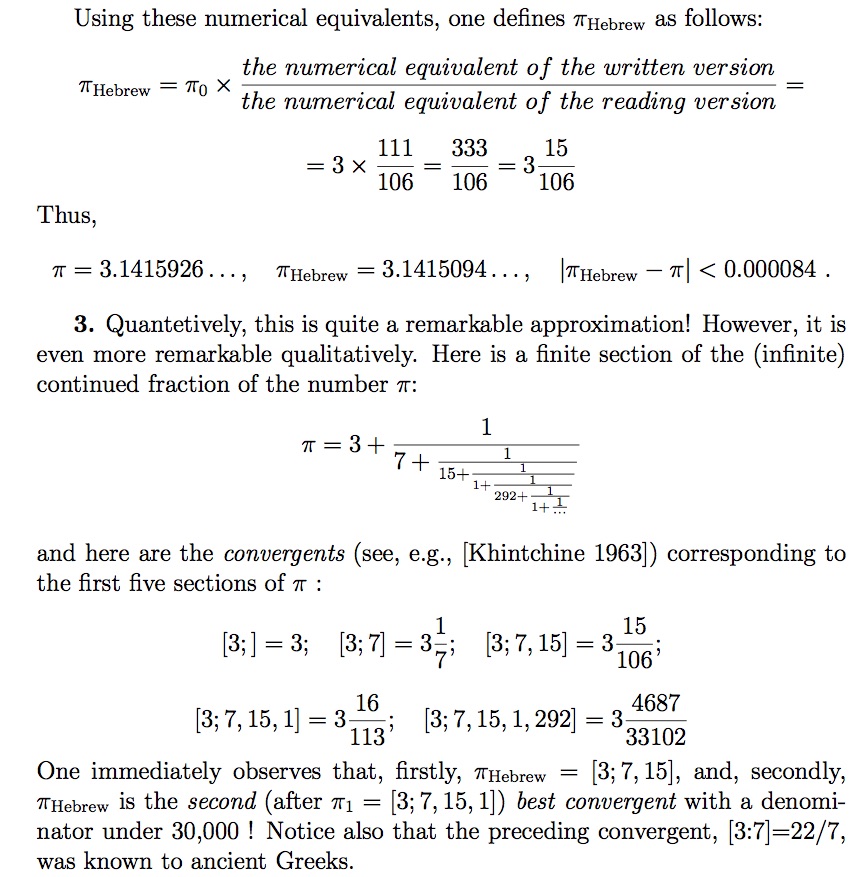

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: סִימָן רַע לְכל הָעוֹלָם כּוּלּוֹ. מָשָׁל לְמָה הַדָּבָר דּוֹמֶה? לְמֶלֶךְ בָּשָׂר וְדָם שֶׁעָשָׂה סְעוּדָה לַעֲבָדָיו וְהִנִּיחַ פָּנָס לִפְנֵיהֶם, כָּעַס עֲלֵיהֶם וְאָמַר לְעַבְדּוֹ: טוֹל פָּנָס מִפְּנֵיהֶם וְהוֹשִׁיבֵם בַּחוֹשֶׁךְ

The Sages taught: When the sun is eclipsed it is a bad omen for the entire world. The Gemara tells a parable. To what is this matter comparable? It is comparable to a king of flesh and blood who prepared a feast for his servants and placed a lantern [panas] before them to illuminate the hall. He became angry at them and said to his servant: Take the lantern from before them and seat them in darkness.

תַּנְיָא רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: כל זְמַן שֶׁמְּאוֹרוֹת לוֹקִין — סִימָן רַע לְשׂוֹנְאֵיהֶם שֶׁל יִשְׂרָאֵל, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמְּלוּמָּדִין בְּמַכּוֹתֵיהֶן. מָשָׁל לְסוֹפֵר שֶׁבָּא לְבֵית הַסֵּפֶר וּרְצוּעָה בְּיָדוֹ, מִי דּוֹאֵג — מִי שֶׁרָגִיל לִלְקוֹת בְּכל יוֹם וָיוֹם הוּא דּוֹאֵג

It is taught in a baraita that Rabbi Meir says: When the heavenly lights, i.e., the sun and the moon, are eclipsed, it is a bad omen for the enemies of the Jewish people, which is a euphemism for the Jewish people, because they are experienced in their beatings. Based on past experience, they assume that any calamity that afflicts the world is directed at them. The Gemara suggests a parable: This is similar to a teacher who comes to the school with a strap in his hand. Who worries? The child who is accustomed to be beaten each and every day is the one who worries.

The Last total Solar Eclipse over America

On Monday August 21st 2017, almost exactly three years ago, my family and I witnessed a total solar eclipse over Charleston South Carolina. It was an unforgettable event. There is another total solar eclipse coming up in a couple of years, and you won’t want to miss it. We will have more to say about that below. But first let’s focus on the science and the superstition of a solar eclipse.

What causes a solar ecplipse according to The talmud?

The classic Talmudic source on the origins of a solar eclipse is found on today’s page of Talmud, in Succah 29a:

תנו רבנן: בשביל ארבעה דברים חמה לוקה: על אב בית דין שמת ואינו נספד כהלכה, ועל נערה המאורסה שצעקה בעיר ואין מושיע לה, ועל משכב זכור, ועל שני אחין שנשפך דמן כאחד

Our Rabbis taught: A solar eclipse occurs on account of four things: Because the Av Beis Din died and was not properly eulogized, because a betrothed woman was raped in a city and none came to rescue her, because of homosexuality, and because of two brothers who were murdered together.

It is challenging to find a common thread to these four events that would satisfactorily relate them to a solar eclipse, and Rashi despaired of doing so: לא שמעתי טעם בדבר—“I do not know of an explanation for this” he write. Neither do we.

What actually causes a solar eclipse?

As we now understand the phenomenon, a solar eclipse occurs when the moon gets in-between the sun and the earth. When it does, it blocks some of the sunlight and casts a shadow on the earth. A person standing in that shadow (called the umbra) will see an eclipse. The time at which the moon is directly between the sun and the earth is also the start of every Jewish month (or close to it, as we will see below). And so it is clear that a solar eclipse can only occur on (or very close to) Rosh Chodesh, the start of the new Jewish month. However, we certainly do not witness a solar eclipse on every Rosh Chodesh. The reason is that the moon’s orbit is inclined at 5 degrees from the sun-earth plane, so that each month the moon may be slightly above, or slightly below that plane. An eclipse will occur only when the three bodies line up on the same plane, which only occurs infrequently.

If we know that a solar eclipse is a regular celestial event whose timing is predictable and precise, how are we to understand this page of Talmud which suggests that it is a divine response to bad Jewish conduct? We have already noted that Rashi was unable to explain the passage, but this did not prevent others from trying to do so.

The Maharal’s unhelpful suggestion

The Maharal of Prague (d. 1609) has a lengthy explanation in his work Be’er Hagolah which, for the sake of clarity, we shall summarize. The Maharal acknowledged that an eclipse is a mechanical and predictable event but he further suggested that if there was no sin, there would indeed never be a solar eclipse. G-d would have designed the universe differently, and in this hypothetical sin-free universe our solar system would have been created without the possibility for a solar eclipse. The conclusion from the Maharal’s writings is that in a sin- free universe, the moon would not orbit as it does now, at a 5-degree angle to the sun-earth plane. But we now need to ask where, precisely, in a sin- free universe, would the moon be? It couldn’t be in the same plane as the sun and the earth, since then there would be a solar eclipse every month. If the moon were, say, 20° above the earth-sun plane, there would still be solar eclipses, though they would be rarer than they are today. The only way for there to be no solar eclipses in the Maharal’s imaginary sin-free universe would be for the moon to orbit the earth at 90° to the sun-earth axis. Then it would never come between the sun and the earth, and there could never be a solar eclipse. But this would lead to another problem. In such an orbit, the moon would always be visible, and so there could never be a Rosh Chodesh. The Maharal’s thought experiment seems to provide more complications than it does solutions.

2. Rabbi Yonason Eibeschutz (d.1764) and his sunspots

Another attempt to explain the Talmud was offered by R. Yonason Eibeschutz (d. 1764). In 1751, Rabbi Eibeschutz was elected as Chief Rabbi of the Three Communities (Altona, Hamburg and Wandsbek), although he was later accused of being a secret follower of the false messiah Shabtai Tzvi. In January of that year Rabbi Eibeschutz gave a sermon in Hamburg in which he addressed the very same problem that Maharal had noted: If a solar eclipse is a predictable event, how can it be in response to human conduct? His answer was quite different.

He suggested that the Talmud in Succah is not actually addressing the phenomenon that we call a solar eclipse. According to R. Eibeschutz, the phrase in Succah "בזמן שהחמה לוקה" (“when there is a solar eclipse”) actually means “when there are sunspots.” Inventive though this is, there are two problems with this suggestion. In the first place, sunspots were almost impossible to see before the invention of the telescope. The first published description of sunspots in Western literature was in 1611 by the largely overlooked Johanness Fabricius and later by a contemporary of Galileo named Christopher Scheiner (though Galileo quickly claimed that he, not Scheiner, was the first to correctly interpret what they were). Because sunspots are so difficult to see with the naked eye, it seems very unlikely (though not impossible) that this is what the rabbis in the Talmud were describing. Second, according to Eibeschutz, sunspots “have no known cause, and have no fixed period to their appearance.” However, and even by the science of his day, this claim is not correct. In fact, both Scheiner and Galileo knew—and wrote—that sunspots were permanent (at least for a while) and moved slowly across the face of the sun in a predictable way. The suggestion that these spots are a response to human activity is therefore difficult to sustain. Furthermore, while a total solar eclipse is strikingly visible to those who are in its shadow, sunspots are, as we have noted, incredibly difficult to see with the naked eye. It would therefore make little sense to declare that these invisible sunspots serve as a warning (סימן רע)to humanity. Finally, the Talmud describes the phenomenon of an eclipse (ליקוי) as being visible in only some places on the earth. While this is a perfect description of a solar eclipse, sunspot activity would be visible from any place on earth, a situation that is clearly not the one described in the Talmud.

3. Rabbi David Pardo (1718–1790)

A different suggestion was offered by R. David Pardo (1718–1790) in his work Chasdei David, published in 1796. R. Pardo acknowledged that most solar eclipses are indeed predictable events, but suggested that there are other kinds of eclipses that cannot in fact be predicted, and it is these kinds of eclipses to which the Talmud is referring. Unfortunately, this suggestion has no factual basis. There are no such phenomena as an unpredictable lunar or solar eclipse, and R. Pardo’s suggestion is untenable.

4. The explanation of the Lubavitcher Rebbe- it’s all about the weather

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, also addressed the Talmudic passage, and in a 1957 responsum he wrote that while a solar eclipse was predictable, the local weather was most certainly not. It could not be predicted whether or not a solar or lunar eclipse would be visible through the clouds, and since it was this aspect that was under Divine control, it presumably could change in response to the local actions of people.

Elegant as this might be, this suggestion, too, has considerable problems. In the first place, the weather is indeed predictable, although of course the ability to predict the weather is relatively limited. But more problematic is the fact that a total solar eclipse will be completely visible whether or not there are clouds. A cloudy day will prevent a viewer on the ground from witnessing the moment of conjunction as the moon covers the disc of the sun (which, I can tell you, is pretty cool), and also prevent him from seeing the stars. However, the other effect of a total solar eclipse— darkness as though it were night—will be just as visible.

On the Molad and Astronomical Conjunction

The last solar eclipse brought to our attention another issue. It occurred on August 21, 2017, when the moon is directly between the sun and the earth (or, more technically, when the sun and the moon have the same elliptical longitude). This started at sunrise over the Pacific Ocean northeast of Hawaii, at 4:48 p.m. UTC, or 6:48 p.m. in Jerusalem. And yet the announced time for the molad of Rosh Chodesh Elul, however, was Tuesday, August 22, at 10:44 a.m. and 15 chalakim—about 16 hours later. That is odd since the molad (lit the birth of the moon) is supposed to be the exact time at which the sun, the earth and the moon all line up, at time called the astronomical conjunction.

“...the molad we announce on the Shabbat preceding Rosh Chodesh represents a theoretical time only, and has no relationship to an astronomical phenomenon. ”

The solar eclipse is therefore a visible reminder that the time of molad we announce on the Shabbat preceding Rosh Chodesh represents a theoretical time only, and has no relationship to an astronomical phenomenon. The announced molad is calculated by using the length between one new moon and the next. This figure assumes that every lunar month is of equal length, 29 days, 12 hours 44 minutes and 3 1/3 seconds. The Jewish calendar is based on the axiom that all future times of the molad are based on the theoretical time for the first molad, which was in Tishrei of the first year of Creation. This is assumed to have occurred on a Monday night, at five hours and 204 chalakim—a time that occurred only in theory since, according to Jewish tradition, the sun and the moon had not been created at that time. To determine the time of any molad since then, we simply add 29 days, 5 hours and 204 chalakim for each month from the primordial Tishrei. But this calculated time differs from the actual length of time between one new month and the next, which is not constant. For this reason, the times announced for the molad are not astronomically accurate—and, as we have seen, this can result in a discrepancy of more than 16 hours between the astronomical conjunction and the calculated Jewish conjunction. (To read more about this problem see our post here.]

HalaKhic Aspects of a Solar Eclipse

There are two categories of questions surrounding a solar eclipse. The first focuses on the technical aspects of the eclipse as a natural phenomenon, and the second on the eclipse as an omen of tragedy.

1. Publicizing the date of a forthcoming eclipse

The Mishnah Berurah rules that it is forbidden to tell another person that a rainbow is visible, because this violates the prohibition of slander (מוציא דבה), since the primordial rainbow appeared after the sins of humanity that caused Noah’s Flood.

And since a solar eclipse is, according to today’s page of Talmud, a sign of human sin, it might be suggested that it would also be forbidden to announce the time of a future solar eclipse. However, unlike a rainbow, a solar eclipse may be entirely predicted, and on the basis of this, Rabbi Avigdor Nebenzahl (b. 1935) ruled that it is permitted to publicize the dates and times of a future eclipse. (See R. Avigdor Nebenzahl, Teshuvos Avigdor HaLevi (Sifrei Kedumim: 2012), p. 249 #105.)

2. Reciting a blessing on seeing a solar eclipse

There is halachic precedent for reciting a blessing on seeing an awe-inspiring vista or event. We make a berachah on seeing the Mediterranean Sea, or a rainbow, on hearing thunder and seeing lightening, and even on seeing a person of exceptional beauty. It is perfectly understandable, therefore, for a person witnessing one of the greatest of nature’s spectacles, to wish to mark the event with a blessing. However, there appear to be no halakhic authorities who would allow a berachah to be recited. Perhaps the first to write about this was R. Menachem Mendel Schneerson. In 1957, he was asked if it was permitted to say a berachah on seeing a solar or lunar eclipse, and his reply was unequivocal:

ידוע הכלל אשר אין לחדש ברכה שלא הוזכרה בש"ס (ב"י או"ח סמ"ו). וי"ל הטעם דאין מברכין ע"ז מפני שהוא סימן לפורעניות הבאה )סוכה כט, א(. ואדרבה צריכה תפלה לבטלה וצעקה ולא ברכה

There is a well-established principle that it is forbidden to institute a blessing that is not mentioned in the Talmud. And some say that the reason that no blessing was instituted is because the eclipse is a bad omen. To the contrary, it is important to pray for the omen to be annulled, and to cry out without a berachah. (Iggerot Kodesh 15:1079.)

R. Schneerson combines a halakhic justification for not reciting a berachah with the classic Talmudic teaching from our page today that a solar eclipse occurs as a result of human sin. However, there are two problems with R. Schneerson’s ruling. First, it is normative Jewish practice to recite a berachah on hearing bad news such as the death of a person, and second, the Talmud does not describe a solar eclipse as an omen of forthcoming disaster. It is a sign of sin, not of punishment.

R. Chaim Dovid HaLevi, Av Bet Din (Chief of the Rabbinic Court) of Tel Aviv and Yaffo, also ruled that we are forbidden to create new berachos, (Aseh Lecha Rav [Tel Aviv, 5749], 150) although he understood the urge to do so:

Our Rabbis instituted blessings over acts of creation and powerful natural events, like lightning and thunder and so on. However, they did not do so for a lunar or solar eclipse. And if only today we could institute a blessing when we are aware that an eclipse is indeed an incredible natural event. But we cannot, for a person is forbidden to make up a blessing. If a person still wants to make some form of a blessing, he should recite the verses “And David blessed...blessed are you, God, the Lord of our father Israel, who performs acts of creation.”

Finally, we should note the opinion of R. David Lau, then the Chief Rabbi of Modi’in, and currently the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel. A certain David Eisen wrote to R. Lau about his experiences of observing the (partial) solar eclipse of 2001 that could be seen in Israel. He had been left wishing to make a blessing for what was, for him, an awe-inspiring cosmic occurrence. R. Lau empathized with Eisen’s feelings, but noted that since the Rabbis of the Talmud had not prescribed a blessing over an eclipse, it was not possible to institute such a blessing today. Rabbi Lau noted that his own religious response to witnessing the eclipse had been to say Psalm 19, “The Heavens tell of G-d’s glory,” and Psalm 104, “My soul will bless G-d.”

3. Marriage and fasting on the day of a solar eclipse

The Chasidic leader R. Zvi Elimelech Shapira of Dinov (b. 1785), wrote in his classic work Bnei Yissaschar that a man should not marry when the moon is waning, “and particularly not during a lunar eclipse, G- d forbid.”(Bnei Yissaschar, Ma’amarei Rosh Chodesh, #2.) He does not mention whether this would apply to a solar eclipse. The Mishnah Berurah also notes the opinion of the Sefer Chasidim that one should fast on the day of a lunar eclipse, although he does not rule on the matter further (Mishnah Berurah #580:2). The matter was more recently addressed by R. Menachem Lang, who notes that it might be forbidden to marry on the day of any kind of eclipse, but ultimately ruled that there is no such prohibition. When a solar eclipse occurs on the same day as Rosh Chodesh, any fast would be forbidden under the general prohibition of fasting on Rosh Chodesh (Mishnah Berurah #580:1).

[Most of this post comes from an essay published in Hakirah in 2017. You can read the entire essay here.]

A SPECIAL ECLIPSE ANNOUNCEMENT FROM TALMUDOLOGY

Here is the great news: there is another total solar eclipse coming soon to North America!

On Monday April 8, 2024 another total solar eclipse will be visible over North America. If the weather cooperates, it will be seen along a narrow path that starts from Mexico's Pacific coast, passes through several American states, and ends on the Atlantic coast of Canada. The rest of mainland United States and Canada, and parts of the Caribbean, Central America, and Europe will see a partial solar eclipse, which is nowhere nearly as spectacular and is often not even noticeable. The next time you will get to see a total solar eclipse in the US after that will not be until August 2045. So plan now!

Image from here

Join Talmudology for the Great American Solar Eclipse II

The Talmudology Excursions Division is in the early stages of planning a special weekend of events in preparation of this amazing experience. As you can see from the map above, Cleveland Ohio will be in the center of the path of the totality, and that is likely where the Talmudology Eclipse Gathering will be.

Sign up below to receive updates about this unique event. We hope to see you in April 2024. (It will be here sooner than you think.)