This post is for the page of Talmud to be studied tomorrow, Thursday July 14th.

כתובות דף ח עמוד ב

רבון העולמים, פדה והצל, מלט, הושע עמך ישראל מן הדבר ומן החרב ומן הביזה, ומן השדפון ומן הירקון, ומכל מיני פורעניות המתרגשות ובאות לעולם, טרם נקרא ואתה תענה, ברוך אתה עוצר המגפה

Master of the worlds, redeem and save, deliver and help your nation Israel from pestilence, and from the sword, and from plundering, from the plagues of wind blast and mildew [that destroy the crops], and from all types of misfortunes that may break out and come into the world. Before we call, you answer. Blessed are You, who ends the plague.

In tomorrow’s page of Daf Yomi, the secretary of Resh Lakish, a man by called Yehuda bar Nachmani, offers four blessings that may be said as part of the meal eaten at a house of mourning. Although the fourth blessing, "Who ends the plague" (עוצר המגפה) is not said usually today, we do have a tradition of giving thanks when a plague comes to an end.

The Prayer of Thanks After the Cholera Epidemic in London, 1850

In the nineteenth century, London was ravaged by a series of brief but intense cholera epidemics that killed hundreds at a time in a matter of days. The infectious agent, we know today, was Vibrio Cholerae. If it finds its way into your intestine, its toxin will cause the cells of your gut to excrete water at a remarkable rate. The result is overwhelming dehydration, and death may follow in a matter of hours. (Water-borne cholera epidemics are still common. After the 2012 Haitian earthquake over 4,000 people died from it. That's 4,000 people who survived the earthquake itself, only to die from drinking water that was infected with cholera.)

Like all epidemics, cholera flares up and then disappears, even when no effective medical interventions are available. It was when one of these devastating outbreaks of cholera had ended, that the Jews of London came together to do what Resh Lakish described. On Nov 1, 1850, they offered a prayer of thanks at the cessation of the plague of cholera.

ידך היתה בבני ארצנו בחלי–רע לאין מרפא רבים חללים הפיל עד שאיש נבוב חת לקול אמות דפק על פתחו וחיל אחז אמין לב בגבורים. אך חנון ירחום אתה, לא לעולם תזנח ולא לנצח תטור אם הבאבת תחבוש, ואם תמחץ ידיך תרפינה. שלחת רוחך ותחלימנו צוית והמגפה נעצרה

“Your hand lay heavily on the inhabitants of this land. Cholera struck many down. The strongest heart trembled at the voice of death sounding at the threshold, and the boldest among the mighty were seized with terror and anguish. But gracious and and merciful are You; Your wrath does not last long, nor does Your anger last for ever. You strike some and heal. You wound but it is Your hand which prepares the calm. In the depths of our terror and affliction You sent Your spirit and there was a pause. You commanded, and the Plague ceased... ”

Why did the cholera epidemic end so quickly? There is, of course a scientific explanation:

[I]t's possible that the V. Cholerae's dramatic reproductive success...had been the agent of its own demise...it quickly burned through its primary fuel supply. There weren't enough small intestines to colonize....It's also possible that the Vibrio cholerae had not been able to survive more than a few days in the well water... With no sunlight penetrating the well, the water would have been free of plankton, and so the bacteria that didn't escape might have slowly starved to death in the the dark, twenty feet below street level...But the most likely scenario is that the bacterium was itself in a life-or-death struggle with another organism: a viral phage that exploits V. cholerae for its own reproductive ends the way V. cholerae exploits the human small intestine. One phage injected into a bacterial cell yields about a hundred new viral particles, and kills the bacterium in the process. After several days of that replication, the population of V. cholerae might have been replaced by phages that were harmless to humans. (Steven Johnson, The Ghost Map, 152).

But this explanation lessens not one bit the religious impulse to give thanks.

THE END OF ONE PLAGUE, THE BEGINNING OF ANOTHER

In 2015 in West Africa, a terrible Ebola epidemic slowly came to an end. Although there was neither an effective vaccine to prevent Ebola, nor an effective anti-viral to treat it, public health interventions there paid off, and life is slowly returned to normal.

Back in the US, at around the same time. another plague began. That one, while far less lethal that Ebola, was all the more tragic; all the more tragic because it is entirely preventable. There were more than 100 cases of measles in January 2015 alone (compared to about 600 for all of 2014), most of them linked to exposure in December at Disneyland in California. I had the measles as a kid. If you were born before the 1970s, it's likely you've had it too. My aunt caught it when she was carrying my cousin, who was born deaf, the result of congenital measles infection. Back then, there was no vaccine. There is now. And don't start with the autism-vaccination thing. There is no link between autism and vaccination. None. Yet in significant numbers, Jewish parents - and some of them educated, are refusing to vaccinate their children. Vaccine denial is not limited to some haredi communities, (though in many cases their vaccination rates are remarkably low). It was seen in affluent neighborhoods with highly educated parents, where the vaccine denial movement has become a cult in which any and all scientific evidence is ignored.

In this daf, the secretary of Resh Lakish offered a Prayer of Thanks when a plague ended. But precisely when did he say these words? At a funeral. The funeral of a young child (ינוקא). The secretary of Resh Lakish offered these words of thanks at a child's funeral, and directed them towards "all Israel" (כנגד כל ישראל), that is, towards the survivors. How ironic it is, that it is the children who were at most at risk in this measles epidemic. And how tragic that they faced the complications of this illness (including pneumonia, diarrhea, encephalitis, subacute sclerosing pan-encephalitis, and death,) because of the reckless behavior of their parents.

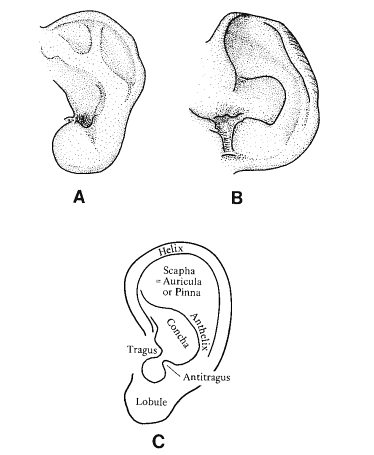

Risk factors of underutilization of childhood immunizations in ultra-orthodox populations. From Muhsen K. el at. Risk factors of underutilization of childhood immunizations in ultraorthodox Jewish communities in Israel despite high access to health care services. Vaccine 2012. 30; 2109–2115

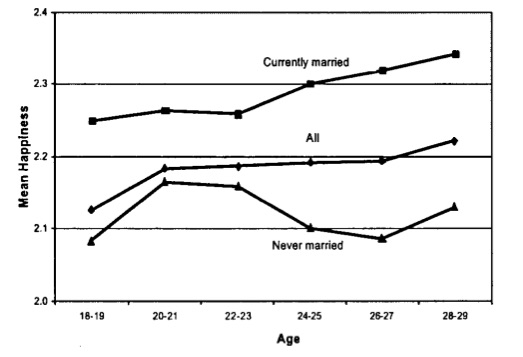

Characteristics of parents who reported vaccine doubts. From Gust D. et al. Parents With Doubts About Vaccines: Which Vaccines and Reasons Why. Gust D. et al. Pediatrics 2008;122: 718–725

Want to read more on vaccine denial and Jewish leadership? Click here for our 2019 article in The Lehrhaus.