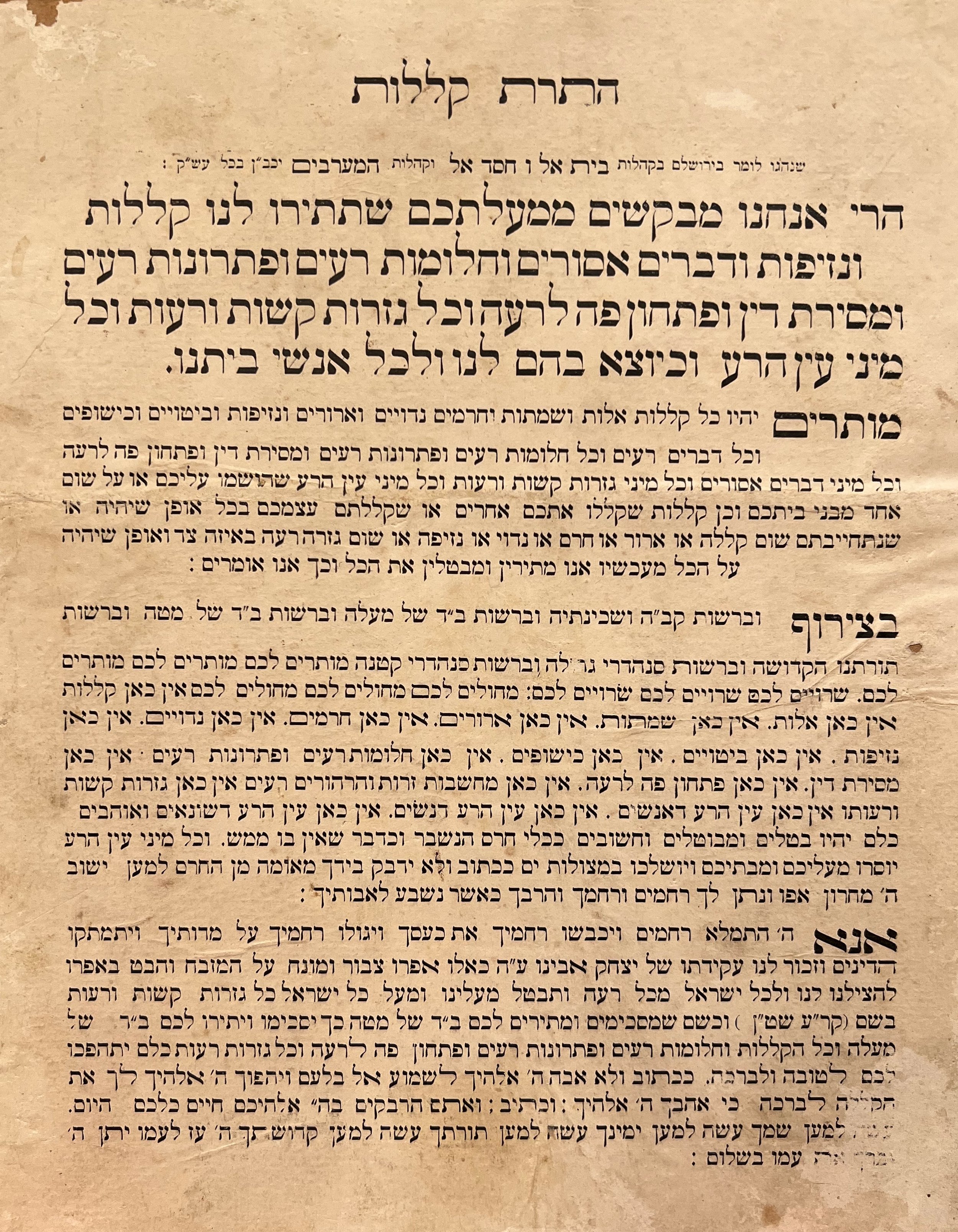

Today we reach the end of the tractate Nedarim, which featured many in-depth discussions on the meaning of words and how they are to be taken seriously. So seriously do we take the concern of inadvertently vowing to do something and then failing do follow through, that the very first words of the Yom Kippur service, Kol Nidre, are a nullification of any and all future vows that may be uttered over the coming year. It has become part of Jewish tradition that on the days leading up to Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur, a ceremonial “release from vows” - hatarat nedarim - is performed.This much is familiar to most readers of Talmudology. But how many are familiar with another ceremony, this one called hatarat klallot - the nullification not of vows, but of curses?

The Old Jewish Cemetery in Marrakesh.

Hatarat Klallot in Marrakesh

A couple of weeks ago I was lucky enough to accompany a group of students from Yeshiva University’s Sacks-Herenstein Center for Values and Leadership on a trip to Morocco. It was while we were volunteering to help restore the Jewish Cemetery that one of the students found several printed leaves titled “Hatarat Klallot” in the community geniza, With the permission of the authorities, the student and I took several of these texts as souvenirs of a sort. But they are much more than that.

As you can see form the text above, the ceremony closely follows the language and style of the much more familiar hatarot nedarim that is performed to this day. But instead of announcing our regret at having vowed and then failing to follow through, hatarot klallot asks us to be released from any curses that others may have placed on us, or that we placed on others.

The text appears to have been composed by Rabbi Chaim Yossef David Azulai, better known by his acronym as the Chida (1724-1806) and may be found in his Tziporen Shamir. The Chida was born in Jerusalem from Moroccan ancestors, and while he was a noted talmudist, his world view was profoundly shaped by the Jewish mystical tradition, known as Kabbalah. Here are the opening words of his Hatarat Klallot (there are various versions), which is recited in front of three others who serve as a makeshift court:

We ask your honors to release us from any curses or rebukes, or forbidden things, or bad dreams and their bad interpretations, and any judgements against us, or any opportunity for bad things to occur, and any harsh or evil decrees, and all evil eyes that may have been cast against us or against any members of our households…

And the acting judges reply:

In the name of the heavenly court and in the name of the earthly court we hereby release you…from the effect of any curse or ill will or evil or any vow or any promise [made against you]…There is no longer any rebuke or any harmful phrase or witchcraft or nightmare or an evil interpretation of dreams. There is to be no trial [of you], there is no opportunity for evil, there are no bad strange thoughts or evil daydreams [against you]. There are no evil decrees, there is no evil eye cast by a man and none cast by a woman. There is no evil eye cast by those who hate you or those who love you. They are all annulled and decreed to be ineffective, as useless as a piece of broken pottery, a thing of no material substance. All types of evil eye are hereby removed from you and from your homes and are cast into the depths of the ocean…

The Chida wrote that this was to be recited before Rosh Hashanah, but if you look carefully at the small print at the top of the image you will read:

It is the custom to say this in the Jerusalem synagogues of Bet El… and in those from the west [i.e. Morocco] every Friday before Shabbat

Presumably this was also a widespread custom in Morocco itself, or at least in Marrakech, where we found a dozen or so of these printed sheets in the geniza.

As we close Nedarim let us pause to remember the power of words to commit, their power to release, their power to curse, and their power to reassure that the future will be bright.