Today, we take a deep dive into baths.

נדרים דף עט, א - פא, א

ואלו נדרים שהוא מפר, דברים שיש בהן ענוי נפש: אם ארחץ ואם לא ארחץ ...אלא דאמרה הנאת רחיצה עלי לעולם אם ארחץ היום, ורבי יוסי סבר: ניוול דחד יומא לא שמיה ניוול

מעיין של בני העיר, חייהן וחיי אחרים - חייהן קודמין לחיי אחרים, בהמתם ובהמת אחרים בהמתם קודמת לבהמת אחרים, כביסתן וכביסת אחרים - כביסתן קודמת לכביסת אחרים, חיי אחרים וכביסתן - חיי אחרים קודמין לכביסתן, רבי יוסי אומר: כביסתן קודמת לחיי אחרים

כביסה אלימא לר' יוסי, דאמר שמואל: האי ערבוביתא דרישא מתיא לידי עוירא, ערבוביתא דמאני מתיא לידי שעמומיתא, ערבוביתא דגופא מתיא לידי שיחני וכיבי

These are the vows [made by a wife] that a husband may revoke: matters that involve self-afflction. For example [a wife made a vow] "If I bathe and if I do not bathe..."

What could this mean? She said The pleasure of bathing is forbidden to me forever if I bathe today. And Rabbi Yossi believes that not bathing for one day is not called repugnance...

If a spring belonged to townspeople, [but it does not supply the needs of everyone, whose needs take precedence?] When it is a question of their own lives or the lives of strangers, their own lives take precedence; the lives of their cattle or the cattle of strangers - their cattle take precedence over those of strangers; their laundering or that of strangers - their laundering takes precedence over that of strangers. But if the choice lies between the lives of strangers and their own laundering, the lives of the strangers take precedence over their own laundering. R. Yossi ruled: Their laundering takes precedence over the lives of strangers...

[The discomfort of not laundering clothes is greater than that of not bathing] according to Rabbi Yossi, as Shmuel taught: filth on the head leads to blindness, dirty clothes leads to dementia, not bathing leads to boils and sores...

Clean Body, Clean Clothes

The passage on today's page in the Talmud seeks to understand the Mishnah (learned yesterday) which taught that a husband may annul his wife's vow if it would interfere with her bathing regime and hence cause her to become, well, smelly and unattractive. In contrast to this, Rabbi Yossi (a student of Rabbi Akivah and who lived in Israel in the second century CE.) taught that this vow cannot be annulled since he understands that it only prevents her from bathing for a single day - and this brief abstinence does not cause her to become repugnant in her husband's eyes. In tomorrow's daf the analysis is completed when it is discovered that Rabbi Yossi, while not seeming to be bothered by a lack of one day of bathing, was indeed very bothered by a lack of clean laundry. How bothered? Well, if it's your water and you only have enough to clean your own laundry or to give an outsider a life sustaining drink, guess who is going to be wearing some clean clothes! Rabbi Yossi was so bothered by dirty clothes that he valued them over life itself (so long as that life was not your own). It seems rather odd, does it not, for Rabbi Yossi to allow a wife to do without bathing for a day and yet hold clean clothing to be really important? To answer this, we need to dive in to the history of bathing.

Jewish, Roman and Early Christian Bathing Habits

The Talmud is replete with statements that emphasize the importance of daily bathing. A תלמיד חכם (scholar) is forbidden to live in a town that does not have at least one bathhouse, and Hillel the Elder taught his students that going to wash in the bathhouse was a מצוה, since there was a responsibility to care for the human body, created as it was in the very image of God. Hillel seems to have left a cleanliness legacy in his family: his grandson, Rabban Gamliel (who lived in the early part of the first century CE.) was so in need of bathing that he allowed himself to wash on the first night after his wife died - an act that was understood to be forbidden. In the Jerusalem Talmud, the precedent of Rabban Gamliel is further analyzed. When a rabbi developed boils during his period of mourning (which the Talmud assumes was due to a lack of washing) a certain Rabbi Yassa allowed him to wash immediately - "for otherwise he could die." Rabbi Yassa extended his ruling to allow bathing on (wait for it...) Tisha Be'Av and Yom Kippur - so long as the bathing was to alleviate discomfort rather than for pleasure.

The famous Greek physician Hippocrates, (died c. 370 BC) wrote about the healing power of warm (and very cold) baths. But as Katherine Ashenburg wrote in The Dirt on Clean, her definitive (and very readable) history of bathing, "...while the Greeks appreciated water...the Romans adored it." The Roman desire of cleanliness and their culture of bathing is of course well known to anyone who has visited a Roman ruin in Israel, Italy or elsewhere. The focus on bathing seems to have changed with the fall of the Roman empire and the rise of Christianity. Ashenburg explains that since the first Christians were Jews, a way of distinguishing themselves was to ignore the Jewish laws of ritual purity, which involved so much hand washing and body dipping. Although ritual purity is not the same as cleanliness, the two became linked, and with the opposition to the Jewish rules of ritual cleanliness, there rose a Christian opposition to bathing. In the middle ages, some monastic orders allowed only three baths a year, "but monks whose holiness trumped cleanliness could decline any or all baths."

“Jesus’ indifference to ritual purity accorded with what later became a wider Christian distrust or neglect of the body.”

What few bathhouses there were in medieval Europe were closed during the years of the Great Plague, since the best science of the day taught that heat and water created openings on the skin, through which the plague would enter. Here, for example is Ambroise Pare (c. 1510- 1590) who served as surgeon to four French kings:

They must close the public hot baths, because on leaving them the muscles and the general tone of the body are relaxed, and the pores are open, and so the vapour of the plague can readily enter the body and cause death at once; there are many cases of this kind.

"Sadly,” noted Ashenburg “the best medical advice of the day probably doomed many people, for the dirtier people were, the more likely they were to harbor Pulex irritants, the flea now believed to have carried the plague bacillus from rats to humans."

As I point out in my new book on Jews and pandemics, bathing was also frowned upon by eastern European Jews in the 1900s.

According to a Jewish doctor from Wolozyn (now Valozhyn, Belarus), who collected folk curios in the course of his work in the field, it was common practice to avoid changing a patient’s sheets, underwear, and clothing; and washing them with clean water (even wiping their face), and even the use of a cold compresses, would be forbidden. There was no question of opening a window or giving the patient a bath . . . Similar precautions were taken in the room where a woman lay in confinement; moreover, her bed linen would not be changed for four weeks (until her next ritual immersion). The foul air in such rooms was thought to be evidence of the presence of the forces of evil and the struggle against sickness as a demonic being.

“Eilizabeth I of England bathed once a month, as she said, “whether I need it or not.” But the seventeenth century raised the bar: it was spectacularly, even defiantly dirty. Elizabeth’s successor, James I, reportedly washed only his fingers, The body odor of Henri IV of France (1553-1610) was notorious, as was that of this son Louis XIII. He boasted, “I take after my father, I smell of armpits”.”

Clean Linens and Rabbi Yossi

While washing the body was generally avoided in seventeenth century Europe, clean clothes were most certainly demanded, especially among the middle and upper classes. "Clean linen" writes Ashenburg, "was not a substitute for washing the body with water - it was better than that, safer, more reliable and based on scientific principles." And here perhaps is an echo of the position of Rabbi Yossi in today's page of Talmud. To be clear: Rabbi Yossi was not arguing that bathing was not important - rather he argued about the length of time a person could forgo a bath and not become "repulsive" to a spouse. But his emphasis on the need for laundered and clean clothes is striking. The Talmud (Nedarim 81a) relates Rabbi Yossi's concerns to a teaching of the physician Shmuel: Filth on the head leads to blindness, dirty clothes leads to dementia, and not bathing leads to boils and sores..." According to Rabbenu Nissim, (a fourteenth century commentator known by his acronym as the Ran), the first and third of these conditions may be cured - but not the dementia caused by dirty clothes. That's why Rabbi Yossi claimed that the water needed to do the laundry was so important. Here's the text of the Ran:

כשגופו מזוהם שאינו רוחץ תמיד מביאו לידי שיחנא וכיבי אבעבועות המכאיבות ולאלו יש רפואות אבל שעמום קשה מהן אלמא כביסה אלימא מרחיצה

Bathing and Healing

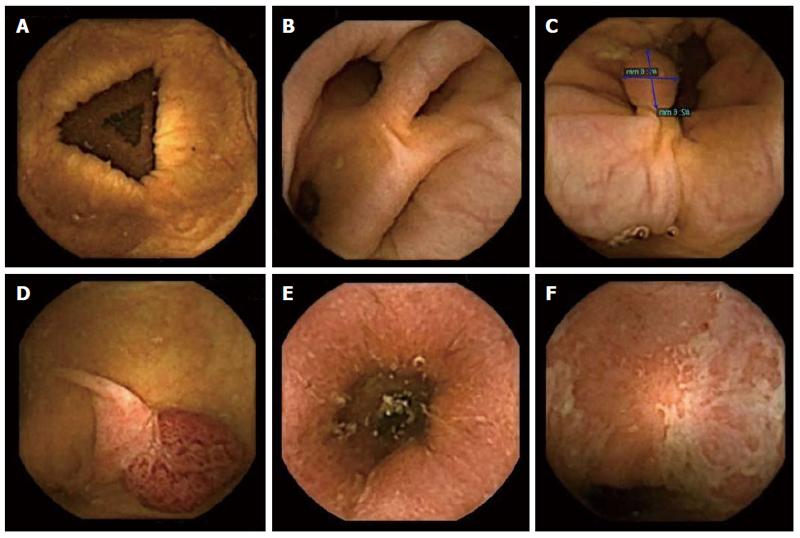

In a 2002 a review of the history of spa therapies was published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, the authors noted that several randomised controlled trials had studied the effects of spa therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis but that "definite judgment about its efficacy is impossible because of methodological flaws in these studies." However, "...overall, the results showed positive effects lasting for three to nine months. Recently, a randomised controlled trial has shown that spa therapy is clearly effective in ankylosing spondylitis. Two intervention groups followed a three week course of spa therapy at two different spa resorts, and were compared with a control group who stayed at home and continued standard treatment consisting of anti-inflammatory drugs and weekly group physical therapy. Significant improvements in function, pain, global wellbeing, and morning stiffness were found for both intervention groups until nine months after spa therapy."

Bathing - and clean clothes - are social customs that have changed and changed again over time. We know of no evidence to support Rabbi Yossi's link between dementia and clean clothes, but at other times and on other cultures clean clothes were indeed valued far beyond a clean body. And today, bathing and doing the laundry still seem like rather good ideas.

“Throughout the ages the interest in the use of water in medicine has fluctuated from century to century and from nation to nation. The (medical) world has viewed it with different opinions, from very enthusiastic to extremely critical, and from beneficial to harmful. Today, spa therapy is receiving renewed attention from many medical specialties and health tourists, and having a revival. However, the exact therapeutic potential of spa therapy still remains largely unknown. Better and more profound scientific evidence for its efficacy is therefore warranted, in particular for its effects on the musculo-skeletal system.”