This is the first of two posts which examine statements of longevity in the Talmud, and how they measure up against data from the contemporary world. Let’s begin with this passage in today’s page of Talmud:

גיטין כח, א

מתני' המביא גט והניחו זקן או חולה נותן לה בחזקת שהוא קיים

גמ' אמר רבא לא שנו אלא זקן שלא הגיע לגבורות וחולה שרוב חולים לחיים אבל זקן שהגיע לגבורות וגוסס שרוב גוססין למיתה לא

איתיביה אביי המביא גט והניחו זקן אפי' בן מאה שנה נותן לה בחזקת שהוא קיים תיובתא ואי בעית אימא כיון דאיפליג איפליג

MISHNAH: If an agent brought a Get and the husband was an old man or was sick, he should still give it to the wife on the assumption that the husband is still alive...

GEMARA: Rava said: [this Mishnah] speaks only of a husband who is not yet eighty years old and of a husband who is ill [but not dying], because most ill people recover. But if the husband is an old man who has already reached the age of eighty, or was in the process of dying, then the Get should not be given to the wife, because most people who are dying do actually die.

Abaye raised the following objection [to Rava from a Baraisa]: 'If an agent was bringing a Get and he left when the husband was old, even a hundred years old, he should give it to the wife on the assumption that the husband is still alive.

This is indeed a refutation [to Rava]. But it is still possible to accept Rava’s position, because [in the case of the Baraisa] if a man reaches such an exceptional age, he is altogether exceptional and unlike other elderly men [and so it may be assumed that the elderly husband is still alive when his appointed agent reaches the wife to give her the Get.]

Was Rava correct in assuming the outer limit of longevity to be around 80 years, and do those who make it into their golden years have good odds of making it even further? Let's take a look.

Nasty, Brutish and Short

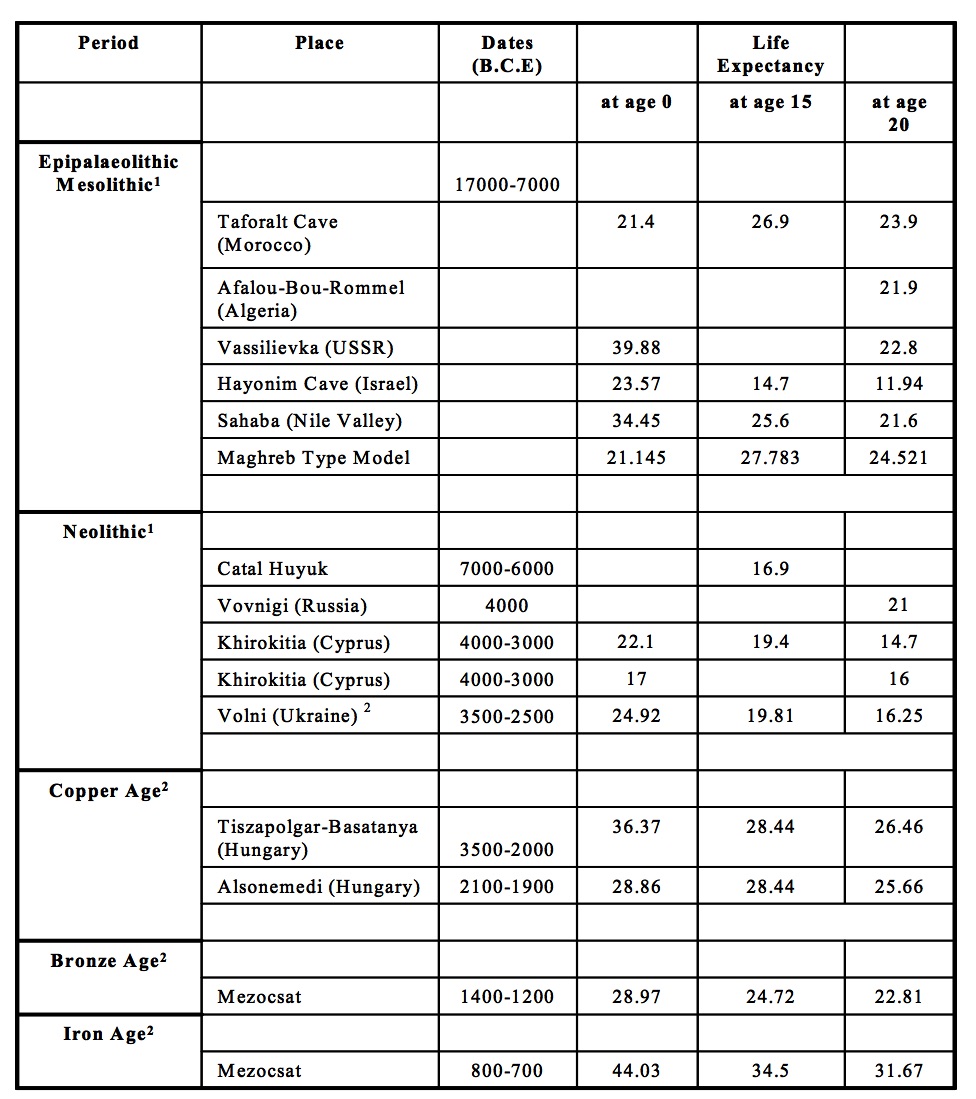

It's quite a challenge to estimate how long most people lived way, way back. But there are some data to suggest that life was, as Thomas Hobbs wrote in his Leviathan "nasty brutish and short". For example, in the Bronze Age - that would be the time in which the Patriarch Abraham, Isaac and Jacob lived lived - life expectancy was about 20-30 years. So yes, Abraham's death at the age of 175, or Sarah's at the age of 127, are both examples of ultra-extreme-turbo-charged longevity.

Life Expectancy: From the Epipalaeolithic Period to the Iron Age. From Oded Galor and Omer Moav.Life Expectancy: From the Epipalaeolithic Period to the Iron Age. Unpublished paper 2005.

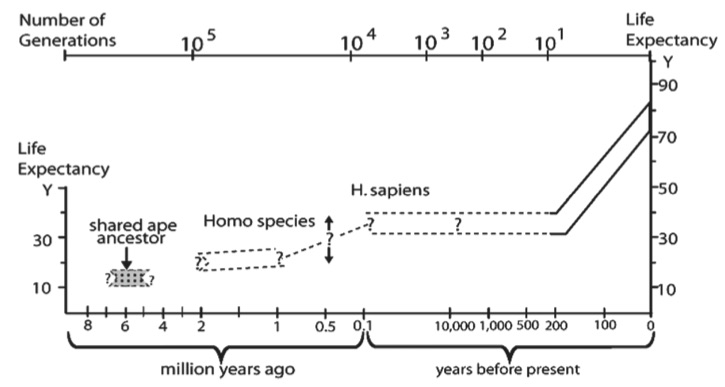

Longevity of Human and Other Primates

Among all the primates, humans have the greatest life expectancy at birth. Before the industrial era, human life expectancy at puberty was about 30 years, about twice that of chimpanzees. Based on evidence from tooth eruption found in skulls it has been possible to estimate the life expectancy of the earliest common ancestor of humans and the great apes. But all this was long ago and far away, and, let's be honest, we really don't know very much about what happened back then. However we do have better data about more recent societies, so let's jump to life under the Romans...

Evolution of the human life expectancy (LE). The LE at birth of the shared great ape ancestor is hypothesized to approximate that of chimpanzees, which are the closest species to humans by DNA sequence data. The LE of chimpanzees at puberty is about 15 years, whereas pre-industrial humans had LE at puberty of about 30 years Since 1800 during industrialization, LE at birth as well as at later ages has more than doubled. LE estimates for ancestral Homo species are hypothesized to be intermediate based on allometric relationships . Ages of adult bones cannot be known accurately after age 30 even in present skeletons .The proportion of adults to juveniles does, however, suggest a shift toward greater LE at birth. The few samples in any case cannot give statistically reliable estimates at a population level. The number of generations is estimated at 25 years for humans.From Finch, C. Evolution of the Human Lifespan, Past, Present, and Future: Phases in the Evolution of Human Life Expectancy in Relation to the Inflammatory Load. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 2012:156 (1). 9-44

Life Expectancy in the Roman Empire

Life Table for the Roman Empire, adapted from Parkin, TG. Demography and Roman Society. John Hopkins University Press 1992.

In Roman society, lifespan remained pretty short, and it was still rather brutish. One-third of all new-borns died within their first year of life. This high infant death rate put the average life expectancy at birth to 20-30 years. But if an infant made it beyond that stormy first year, her projected life expectancy was 33 years. Indeed as you got older, your projected life expectancy increased: if you made it to the age of 45 (and only 6% of the population did) then your projected life expectancy was whopping 61 years, as you can see in the chart. However, very few reached the age of 60, and it is estimated that fewer that 1 in 1,000 (0.1%) lived to age 80. (By comparison, today in Israel over 3% of the population is over 80. In the US its almost 4%.) Based on a number of sources, the historian John Barclay wrote "that people who died in their 60s would be considered to have lived a full life."

Life Expectancy in the Middle Ages and Beyond

Life Expectancy (at birth) in England 1540 -1870. From Wrigley, E.A., and R.S. Schofield. The Population History of England 1541-1871: A Reconstruction Harvard University Press,1981.

Life in the middle ages was not much better. Life expectancy at birth was around 35 years. As urbanization increased and people began to live in closer proximity to one another, the mortality risk increased. Two Israeli scholars estimate that "...life expectancy at birth fell from about 40 at the end of the 16th century to about 33 in the beginning of the 17th century while mortality rates increased by nearly 50%." Life expectancy continued to remain low by modern standards over the next few centuries, although there was an upward trend.

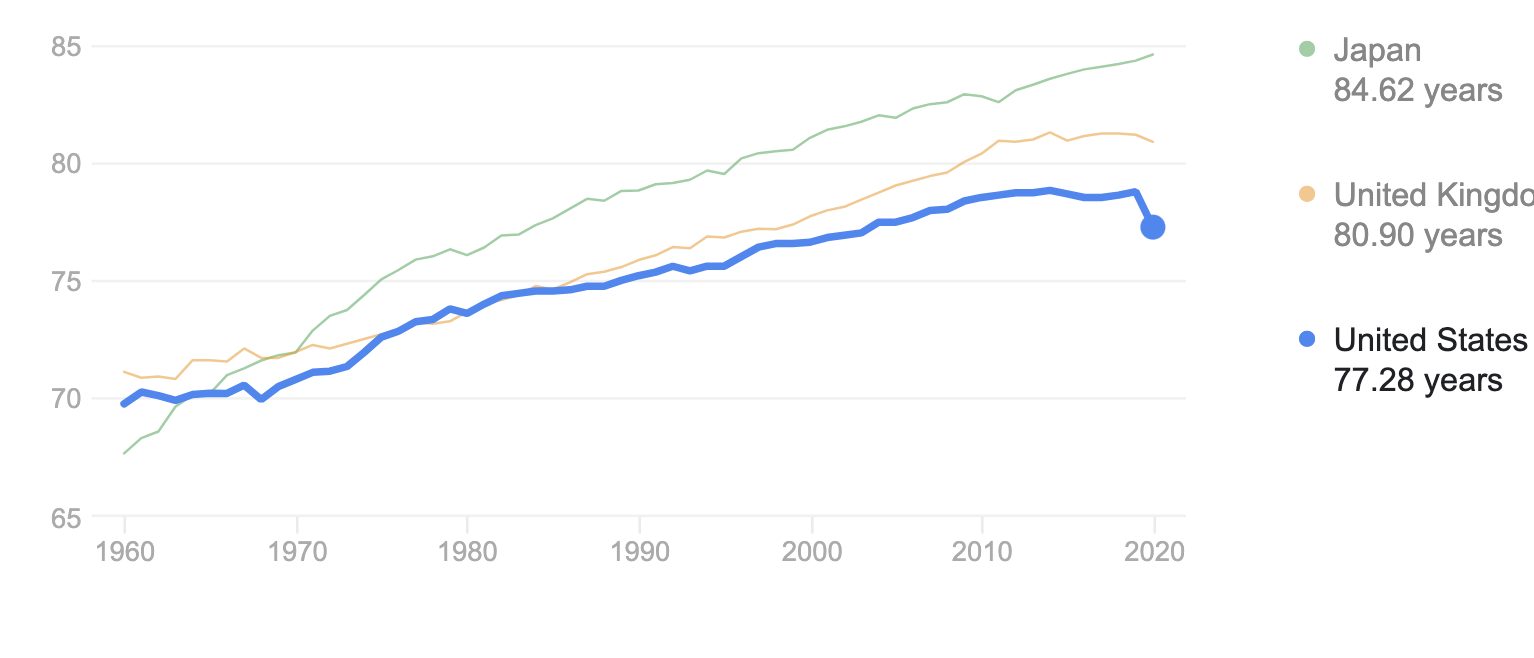

Life Expectancy in the Modern World

Things have gotten much better, very quickly. In the US the average length of life was about 47 years in 1900. Today it is almost double that. This is true for all of the economically developed countries, thought if you want to maximize your chances for a long life, you should live in Monaco; the life expectancy is almost 90 years. But unfortunately only about 30,000 people live there. (This data comes from the CIA, so it must be true.) Although there remains a large disparity in life expectancy between the developed world and Africa, life expectancy is increasing across the globe as a whole.

By Rcragun (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Sadly, for each of the last two years, life expectancy in the US actually declined. As you can see from the graph,

This was the first time it had done so in over two decades. According to the CDC, these declines

are largely driven by the pandemic. COVID-19 deaths contributed to nearly three-fourths or 74% of the decline from 2019 to 2020 and 50% of the decline from 2020 to 2021. An estimated 16% of the decline in life expectancy from 2020 to 2021 can be attributed to increases in deaths from accidents/unintentional injuries. Drug overdose deaths account for nearly half of all unintentional injury deaths. The most recent data reported by NCHS showed more than 109,000 overdose deaths in the one-year period ending in March of 2022.

It’s hard to believe it, but the US is actually going backwards. Perhaps we should all be moving to Japan….

Back to the Talmud

In the passage from the Talmud with which we opened, Rava suggests that a man who has reached eighty is at the very limit of his natural life-span, and may die at any time. If such a person sent an agent to end his marriage - and presuming the trip was relatively long - we cannot assume the elderly husband will still be alive by the time the agent reaches his destination. Rava's assumption is supported by the evidence we have reviewed here. Today, life expectancy in the economically advanced nations hovers right around 80 years, and so Rava's 80 year suggestion seems particularly fitting. But will it remain so in the future? Over the last century the average length of life doubled: could this happen again over the span of the present century? There is no end to "experts" predicting a huge increase in longevity, but for the foreseeable future a slow increase to around 100 years (at least in the developed nations) is certainly possible. This is not to suggest that Rava's estimates were only correct for us today. It would seem in that in many earlier societies, eighty years was a reasonable guess for the outer limit of how long it is possible to live.

There's one other point. Abaye objected to Rava by citing a Baraisa: "If an agent was bringing a Get and he left when the husband was old, even a hundred years old, he should give it to the wife on the assumption that the husband is still alive." To reconcile this with Rava, the Talmud suggests that once a person has reached an old age, he has shown himself to be "exceptional" (איפליג). Actuarial studies today show that this is indeed the case - and it is certainly likely to have been true in Rava's time. (He died around the age of 70 in 352 CE in Babylonia). In Roman times, although chances were against you living to 50 - if you did make it to that birthday you could expect to live a further eleven years. And take a careful look at the chart below, which shows life expectancy today once you make it to 65 years of age or better.

Estimates of life expectancy at selected ages, in two longitudinally followed US populations for persons who remain fully functional. Values in parentheses represent the average lifespan (mean age at death). From Manton KG, Stallard E, Tolley HD. Limits to human life expectancy: evidence, prospects and implications. Population and Development Review 1991. 17 (4): 603-637.

Today, if you make it to 85, you might expect another 20 years of life (or only 11 if you are man). So the Talmud is spot on - once you prove yourself to have exceptional longevity, the future looks pretty good. Until it doesn't.

Next time on Talmudology, Longevity II:

"If you hear that your friend died, believe it. If you hear that he became wealthy, don't believe it."

“Our days may come to seventy years, or eighty, if our strength endures;”

![By Rcragun (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54694fa6e4b0eaec4530f99d/1452268160939-PHU1CQR7IWO804I736PN/image-asset.png)