On today’s daf, we read this:

סנהדרין צד, א

״לְםַרְבֵּה הַמִּשְׂרָה וּלְשָׁלוֹם אֵין קֵץ וְגוֹ׳״. אָמַר רַבִּי תַּנְחוּם: דָּרַשׁ בַּר קַפָּרָא בְּצִיפּוֹרִי, מִפְּנֵי מָה כל מֵם שֶׁבְּאֶמְצַע תֵּיבָה פָּתוּחַ, וְזֶה סָתוּם? בִּיקֵּשׁ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא לַעֲשׂוֹת חִזְקִיָּהוּ מָשִׁיחַ, וְסַנְחֵרִיב גּוֹג וּמָגוֹג

“For the increase of the realm and for peace without end there be no end, upon the throne of David, and upon his kingdom, to establish it and uphold it through justice and through righteousness, from now and forever; the zeal of the Lord of hosts does perform this” (Isaiah 9:6). Rabbi Tanchum says that bar Kappara taught in Tzippori: Why is it that every letter mem in the middle of a word is open and this mem, of the word lemarbe, is closed? It is because the Holy One, Blessed be He, sought to designate King Hezekiah as the Messiah and to designate Sennacherib and Assyria, respectively, as Gog and Magog, all from the prophecy of Ezekiel with regard to the end of days (Ezekiel, chapter 38), and the confrontation between them would culminate in the final redemption.

This verse comes right after the far more well-known one (at least in translation): “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government is upon his shoulder: and his name is called Wonderful…” These of course are the words to Handel’s most famous composition: the Hallelujah chorus in The Messiah, only in context they apply to King Hezekiah, (b. 741 CE), the thirteenth King of Judah.

It is not immediately clear how putting a final ם in the middle of the word achieves the meaning that Bar Kappara attributed to it. Here, as usual, Rashi is helpful, and he gives three ways of understanding the homily:

מ"ם שבתיבת למרבה המשרה סתום לכך נסתם לומר נסתמו הדברים שעלו במחשבה ולא נעשה ל"א שביקש הקב"ה לסתום צרותיהן של ישראל שבקש לעשותו משיח ומורי רבי פירש לפי שנסתם פיו של חזקיה ולא אמר שירה

The ם is closed as if to say, this matter is over - that which he thought of doing [making King Hezekiah the Messiah] was never actually done. Another explanation that God wished to to close the claims of Israel who wanted to make King Hezekiah the Messiah [and this is hinted to by the closed form of the letter ם]. And my teacher taught me that it means that the mouth of Hezekiah was closed and he could no-longer sing words of praise [as he should have done when he was delivered from the threat to him by the Assyrians.

Today on Talmudology we will explore the question posed by Rabbi Tanchum, who was a third century rabbi who lived in Israel, in the name of his reacher Bar Kappara, who was active in Caesarea around 180-220 CE. Without resorting to eschatology, why is there is the word spelled לםרבה, and not how we would write it today - למרבה?

The leningrad codex

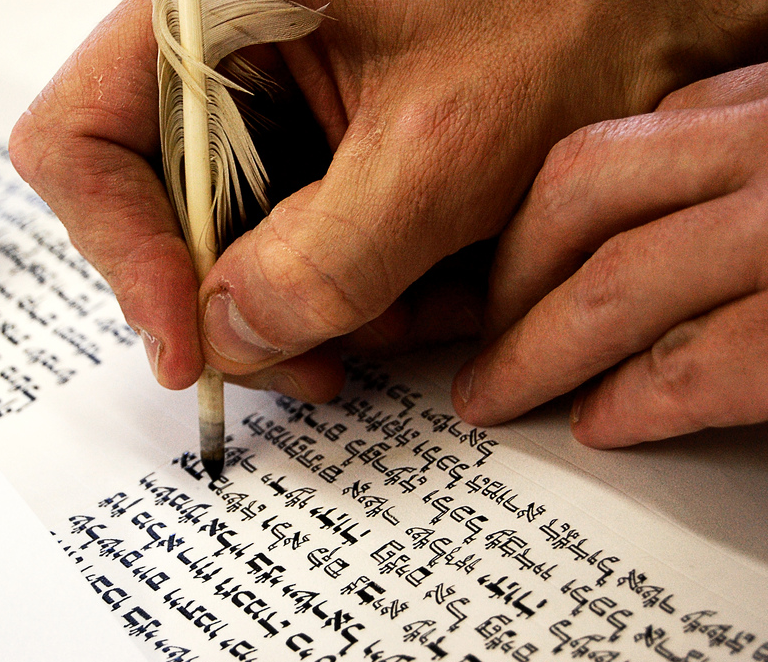

The Leningrad Codex is the oldest known complete Hebrew manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. (because the The כֶּתֶר אֲרָם צוֹבָא - or in English the Aleppo Codex, is not complete). It was completed in 1008 in Cairo. Here is a picture of verse from Isaiah:

Leningrad Codex Isaiah 9:6

As you can see, the word appears with the final ם, as we find in the Talmud, although it is not clear from the positioning of the letters if this is one word or two. In the margin is a note that tells the reader to read it as one word: למרבה ק׳, but it still looks like one word in the body of the text: לםרבה.

Can we go back in time even further? Why yes, we can.

The Aleppo Codex

The Aleppo Codex was written in Tiberius around 920 CE and it is the oldest extant Hebrew copy of our Bible. Sadly, it is missing 40% its original pages (mostly from the Torah section), which were either burned during the anti-Jewish riots in Aleppo in 1947 or were pilfered and kept likely as good luck charms. In it, the word is written as two, with a final ם in the first word (remember that).

The Aleppo Codex, Isaiah 9:1b-8a

Can we go back even earlier? Yes we can, to the oldest extant copy of the Book of Isaiah.

The (Great) Isaiah scroll

The Isaiah Scroll, also known as the Great Isaiah Scroll, is one of the seven original Dead Sea Scrolls found by Bedouin shepherds in 1946. It is designated 1QIsaa as a kind of scientific identification, and has been carbon-dated (four times!) and dated using paleography. The former suggest that the scroll was written between 335-324 BC and 202-107 BC, while the latter method dates the scroll’s birthday to 150-100 BC. And in this scroll, the word למרבה definitely appears as two - למ רבה, but no final ם is involved. Take a look:

The Great Isaiah Scroll, 1QIsaa, Isaiah 9:6

To be clear, there are no notes or textual variations written into the Isaiah Scroll (like there are in the Leningrad Codex) so although the final letter of the first word is a regular מ they would be read as two separate words.

summary of the Different Versions

Two words, final לם רבה :ם – Aleppo Codex

Probably one word, final ם in the middle: לֹםרבה- Leningrad Codex

Two words, regular למ רבה - Isaiah Dead Sea Scroll

The Mesorat Hamesorot of Eliyahu Ashkenazi

Eliyahu ben Asher Ahskenazi (1469-1549) was one of the great grammarians of the early modern period (or late Middle Ages, you choose) and in his work on grammar, Mesorat Hamesoret - he wrote this (starting at the little pointing hand in both the Hebrew and English translation):

Mesorat Hamesoret, ed. Ginzburg, London 1867, 193.

With no qualms, Rabbi Eliyahu Ashkenazi took on a passage of Talmud that we study today, and thought that Ben Kappara’s homily was based on a simple error. The text is read (and that’s the important factor) as לם רבה and it means “to them is great.” No need for homiletic eschatology. I don’t know what he would have made of Leningrad or Aleppo Codices or of the Dead Sea Scroll, but at least two of them support his thesis. And what of Bar Kappar’s sermon? Why, that is for you to decide.