במדבר 34:12

וְיָרַד הַגְּבוּל הַיַּרְדֵּנָה וְהָיוּ תוֹצְאֹתָיו יָם הַמֶּלַח זֹאת תִּהְיֶה לָכֶם הָאָרֶץ לִגְבֻלֹתֶיהָ סָבִיב׃

The boundary shall then descend along the Jordan and terminate at the Dead Sea.

That shall be your land as defined by its boundaries on all sides.

The Dead Sea is mentioned in the Torah several times. It first appears in Bereshit (14:3) when five kings joined together in a battle “at the Valley of Siddim, now the Dead Sea.”

כל־אֵלֶּה חָבְרוּ אֶל־עֵמֶק הַשִּׂדִּים הוּא יָם הַמֶּלַח

Later in the Bible the Dead Sea is called יָם הָעֲרָבָה and הַיָּם הַקַּדְמֹנִי, while in the Talmud it is called יַמָּא דִסְדוֹם.

The Desolate Dead Sea

In masechet Nazir, the Dead Sea is described as an ultimate place of no return. There the Talmud asks about the fate of various offerings (or money set aside to buy these offerings) that were designated to be brought to the Temple in Jerusalem, but which for one reason or another, could not in the end be donated. Consider for example a father who declared that his son would be a nazarite, and set aside money to bring the associated Temple offerings. However, the son decided he did not want the ascetic life thank you very much, and declined to become a nazarite. What then should become of the money set aside? If the father had set aside the money specifically for the purchase of a chatas - חטאת - a sin offering - he is rather out of luck. The Mishnah states that the money must be cast into the Dead Sea - that is, it cannot be used for any purpose. (This is because the הטאת can never be offered as a voluntary sacrifice, and since the son will not become a nazir, the money cannot be used for a voluntary sacrifice- or any other purpose.)

משנה נזיר כח, ב

היו לו מעות סתומין יפלו לנדבה מעות מפורשים דמי חטאת ילכו לים המלח

If he had set aside unspecified funds [for his son to bring as a nazir, and the son declined to follow through], they may be used for voluntary offerings. If he had set aside specified money [for a chatas sacrifice], the money is thrown into the Dead Sea...

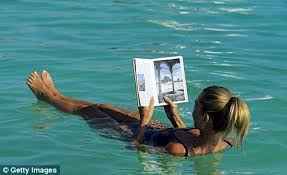

The Formation of the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea lies on a boundary between the Arabian tectonic plate and the Sinai sub-plate, which is part of the larger African tectonic plate. In 1996 Garfunkel and Ben-Avraham published a paper on The Structure of the Dead Sea basin. They note that the Dead Sea rift was formed when the two tectonic plates moved apart from each other, creating a hole in the middle. The Dead Sea is one of the most saline lakes in the world, containing more than 30% of dissolved salts, mostly sodium, calcium and magnesium, potassium and bromine; it is almost ten times more saline than the oceans. The lake lies about 400m below sea level, and in some places the lake is as deep as 300m (for those of you in the US, that is almost 1,000 feet). It is these salts that make the lake so seemingly inhospitable to life, and explain why the rabbis chose the Dead Sea as an example (perhaps the example) of the place to throw the money set aside for a sacrifice that could not be brought. Once the coins were thrown into the murky depths of the lake, they would sink into the silt, rust, and never be found. The Dead Sea is a metaphor for a place without life, which is probably why the Mishnah also rules that into it should be thrown any vessel on which there is an idolatrous images. They will simply never be found again.

עבודה זרה מב, ב

המוצא כלים ועליהם צורת חמה, צורת לבנה, צורת דרקון - יוליכם לים המלח

If one finds vessels on which is the likeness of the sun, the moon or a dragon [all of which were used for idolatry], the vessels should be thrown into the Dead Sea...

“The name “Dead Sea” is of relatively recent vintage. It was first introduced by Greek and Latin writers such as Pausanias (160-180 AD.) Galen (2nd century AD) and Trogus Pompeius 2nd century AD.)”

Life in the Dead Sea

It is fascinating to note that while we refer to the lake as the Dead Sea, as we have seen, it is not called this in the Hebrew Bible or the Talmud. Rather, it is the Salt Sea - ים המלח - with no reference to anything about it being dead. This choice turns out to have been a good one, for although the lake seems to be devoid of any life, there is life within it.

“The increased salinity and the elevated concentration of divalent ions make the Dead Sea an extreme environment that is not tolerated by most organisms. This is reflected in a generally low diversity and very low abundance of microorganisms.”

Microorganisms were first discovered in the Dead Sea in the 1930s, and since then bacteria have been isolated in both the sediment and the water, albeit at low concentrations. However a series of dives in June 2010 revealed a complex system of freshwater springs that feed the lake, and surrounding these springs are bacterial communities with much higher densities, and much greater cell diversity, than was previously known. (You can watch a two-minute video of divers at the bottom of the Dead Sea here. It is amazing to realize that they are the first humans to see the depths of the Dead Sea). An international team of researchers described the findings from these dives in a paper titled Microbial and Chemical Characterization of Underwater Freshwater Springs in the Dead Sea, that was published in 2012. The colonies of cells that surround the freshwater springs are up to 100 times more dense than those found in the ambient water of the Dead Sea, and include bacteria that consume sulfides, and those that metabolize iron and nitrates. The authors conclude that the underwater system of springs that feed the Dead Sea are an "unknown source of diversity and metabolic potential."

Graphical representation of the sequence frequency in the studied Dead Sea samples, showing major detected phyla and families of different functional groups of Bacteria. From Ionescu D, Siebert C, Polerecky L, Munwes YY, Lott C, et al. (2012) Microbial and Chemical Characterization of Underwater Fresh Water Springs in the Dead Sea. PLoS ONE 7(6): e38319.

Despite these findings of life, the Dead Sea is still in trouble. Its level is dropping at the rate of about three feet per year, and its surface area is now only 600 Km2, down from over 1,000 Km2 in the 1930s. The prophecy of Ezekiel (47:8-9) that the water of the Dead Sea would be replaced with fresh water in which great numbers of fish will live is still a long, long way off.

יחזקאל פרק מז, ח-ט

ויאמר אלי המים האלה יוצאים אל הגלילה הקדמונה וירדו על הערבה ובאו הימה אל הימה המוצאים ונרפאו ונרפו המים: והיה כל נפש חיה אשר ישרץ אל כל אשר יבוא שם נחלים יחיה והיה הדגה רבה מאד כי באו שמה המים האלה וירפאו וחי כל אשר יבוא שמה הנחל

He said to me, "This water flows toward the eastern region and goes down into the Arabah, where it enters the [Dead] Sea. When it empties into the sea, the salty water there becomes fresh.Swarms of living creatures will live wherever the river flows. There will be large numbers of fish, because this water flows there and makes the salt water fresh; so where the river flows everything will live...(Ez. 47:8-9)