דברים 3:11

כִּי רַק־עוֹג מֶלֶךְ הַבָּשָׁן נִשְׁאַר מִיֶּתֶר הָרְפָאִים הִנֵּה עַרְשׂוֹ עֶרֶשׂ בַּרְזֶל הֲלֹה הִוא בְּרַבַּת בְּנֵי עַמּוֹן תֵּשַׁע אַמּוֹת ארְכָּהּ וְאַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת רחְבָּהּ בְּאַמַּת־אִישׁ׃

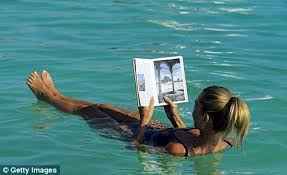

Only King Og of Bashan was left of the remaining Rephaim. His bedstead, an iron bedstead, is now in Rabbah of the Ammonites; it is nine cubits long and four cubits wide, by the standard cubit!

We first met King Og in Bamidbar (Numbers) 21, where he was the Amorite king of Bashan, and where the Israelites quickly defeated him in battle.

במדבר 21: 32–34

וַיִּפְנוּ וַיַּעֲלוּ דֶּרֶךְ הַבָּשָׁן וַיֵּצֵא עוֹג מֶלֶךְ־הַבָּשָׁן לִקְרָאתָם הוּא וְכל־עַמּוֹ לַמִּלְחָמָה אֶדְרֶעִי׃ וַיֹּאמֶר יְהֹוָה אֶל־מֹשֶׁה אַל־תִּירָא אֹתוֹ כִּי בְיָדְךָ נָתַתִּי אֹתוֹ וְאֶת־כל־עַמּוֹ וְאֶת־אַרְצוֹ וְעָשִׂיתָ לּוֹ כַּאֲשֶׁר עָשִׂיתָ לְסִיחֹן מֶלֶךְ הָאֱמֹרִי אֲשֶׁר יוֹשֵׁב בְּחֶשְׁבּוֹן׃ וַיַּכּוּ אֹתוֹ וְאֶת־בָּנָיו וְאֶת־כל־עַמּוֹ עַד־בִּלְתִּי הִשְׁאִיר־לוֹ שָׂרִיד וַיִּירְשׁוּ אֶת־אַרְצוֹ׃

They marched on and went up the road to Bashan, and King Og of Bashan, with all his people, came out to Edrei to engage them in battle.But the Lord said to Moses, “Do not fear him, for I give him and all his people and his land into your hand. You shall do to him as you did to Sihon king of the Amorites who dwelt in Heshbon.” They defeated him and his sons and all his people, until no remnant was left him; and they took possession of his country.

The Torah does not directly tell us Og’s height. Instead it mentions the dimensions of his apparently famous iron bed: “it is nine cubits long and four cubits wide, (by the standard cubit).” A cubit is somewhere around 18 inches (45cm), which would mean that his bed was six feet wide and over 13 feet wide. Why mention this detail? Today on Talmudology we will study two answers to this question. The first comes from the famous Portuguese exegete Isaac Abarbanel (1437-1508), and the second from a professor of Hebrew and Ancient Semitic Languages who sadly passed away barely two months ago.

The Abarbanel

Let’s start with the Abarbanel. Og seems to have been one of the last remaining descendents of the mysterious Nephilim, but why mention him at all? After all, he had been soundly defeated back in Bamidbar 21. Abarbanel provides a few answers:

ונתן ראיה שנית על גבורתו והוא אמרו הנה ערשו ערש ברזל. רוצה לומר שהערש הוא שוכב עליו לא היה מעץ כי לא יוכל העץ לסבול כבדותו בעת השינה אבל היה מברזל. והנה העד בזה הוא החוש שעוד היום הזה לאות ולמופת ברבת בני עמון. וכן אמרו באלה הדברי' רבה רבי אבהו בשם רשב"י אמר לא ראה עוג מימיו לא כסא של עץ ולא ישב על עץ מימיו שלא היה נשבר ממשאו אלא כל תשמישיו מברזל היו

The Torah emphasises his large stature by describing his iron bed. It teaches that the bed was not wooden, because it would not have been able to support Og’s enormous weight as he slept. For this reason, the bed was made of iron. That is why the Torah also mentions that the bed can be seen to this very day, “in Rabbah of the Ammonites”….

The detail about the iron bed is there to remind the reader that although Og had been defeated, he was a giant of a person. Literally. That is why it had been necessary to tell the Israelites “not to fear” (אַל־תִּירָא אֹתוֹ) him. Because he was fearsome. Then the Abarbanel continues:

והביא ראיה שלישית על גבורתו מגודל גופו. ויבאר זה מן גודל הערש שהיה ט' אמות ארכה וד' אמות רחבה. ובאלה הדברי' רבה אמרו משמיה דרשב"ל שעוג מנוול היה שהי' רחבו קרוב לחצי ארכו ואין בריות בני אדם אלא רחבם שליש ארכם וגלית הפלשתי היה נערך באבריו ולזה נקרא איש הביני'. רוצה לומר הנבנה כראוי באבריו. והרב המורה כתב בפרק מ"ז חלק ב' מספרו שלא אמרה התורה זה כמפליג כי אם על צד ההגבלה והדקדוק כי זכרה קומתו בערש שהיא המטה. ואין מטות כל אדם כשיעורו אבל המטה היא תהיה לעולם יותר גדולה מהאיש השוכב עליה. והנהוג שהיא יותר גדול' ממנו. כשליש ארכו. ואם כן שהיתה מטת עוג ט' אמות ארכה תהיה מדת עוג ו' אמות. ואמרו באמת איש איננו באמת עוג כמו שכתוב רש"י ז"ל. כ"א באמת כל איש ממנו והיה עוג אם כן כפל איש אחר. וזה בלי ספק מזרות אישי המין ואינו מן הנמנעות. הנה א"כ היה זה שיעור גדול יוצא מהמנהג הטבעי וכפי שעור הנושא יהיה הכח אשר בו וכל זה ממה שיורה על גודל התשועה האלהית אשר עשה במלחמה זאת

There is a third piece of evidence that Og was a giant. It comes from the size of his bed, which was 9 amot long and 4 amot wide. And in the Midrash Rabba it was said in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Levi that Og was physically deformed, in so far as his arm span was almost half of his height. Uusually, the arm span is about a third of the height…Maimonides in his Guide for the Perplexed wrote that in fact the Torah gives these unusual details [about the size of his bed] to indicate a physical weakness. It did so by describing his height in relation to his bed. Most beds are not the same size as a person; usually they are slightly larger, and about a third as wide as they are high...Og was about twice the height of most people. And this is most certainly a deformity, and not something of beauty. His height was far greater than is usually found, and he was proportionally far stronger. All of these details emphasize God’s salvation in this war…

So for the Abarbanel, the details of the iron bed are provided to draw attention to Og’s unusual physical appearance and large stature. Fair enough, though why not just write “he was a really big king"?” After all, when we read the story of another giant, one named Goliath, there is no mention of how big a bed he slept in. The Bible just tells us his height:

שמואל א, 17:4

וַיֵּצֵא אִישׁ־הַבֵּנַיִם מִמַּחֲנוֹת פְּלִשְׁתִּים גלְיָת שְׁמוֹ מִגַּת גבְהוֹ שֵׁשׁ אַמּוֹת וָזָרֶת׃

A champion of the Philistine forces stepped forward; his name was Goliath of Gath, and he was six cubits and a span tall.

For another stab at the question of why Torah mentions that iron bed, let’s turn to a more recent academic explanation.

About that Big Iron Bed

Abarbanel believed that the bed was made of iron because only that metal could support Og’s enormous weight. But Professor Allan R. Millard, who sadly died two months ago, had a different approach. Lillard was a British orientalist, Rankin Professor of Hebrew and Ancient Semitic languages, and Honorary Senior Fellow at the School of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology. Here is why he thought the Bible would include this detail:

First, we should not think of Og’s bedstead as being of solid iron. Most likely, it was decorated with iron. The situation with ivory is an obvious analogy. The Hebrew Bible contains references to “a throne of ivory” (kisse sen, 1 Kings 10:18; 2 Chronicles 9:17), to “beds of ivory” (mittot sen, Amos 6:4) and even “a house” and “palaces of ivory” (bet hassen, 1 Kings 22:39; hekle sen, Psalm 45:8). Cuneiform texts also mention ivory furniture, best known being Sennacherib’s list of tribute paid by Hezekiah, king of Judah, which included “beds of ivory.” Archaeological discoveries at Samaria and in Assyrian towns have demonstrated that this furniture was not made of ivory, any more than Ahab’s house was; rather, the ivory served as decoration, plating, veneer and paneling. The same could be true of Og’s bed of iron.

Assyrian texts even record “a bed of silver” and other furniture of precious metal. Here, too, the object was not solid metal. The reference is to a method of enhancing wooden pieces, so that, in some cases, the woodwork might be completely covered. A chair and a bed of wood overlaid with ivory in this way were recovered from a tomb at Salamis in Cyprus, dated to about 800 B.C.

An “iron bed” in an ancient Near Eastern context, therefore, is surely to be understood as a bed adorned with iron.

Ok. Big deal. So it had some kind of iron overlay. But why does the Torah tell us that it could still be seen at Rabbah? Was that a place to take the kids when it was raining and they were bored? The good professor thought that the answer was simple:

At that time iron was a kind of precious metal! And Og’s bed was especially large.

The Late Bronze Age ended and the Iron Age began, according to the standard archaeological chronology, about 1200 B.C. That does not mean that before that particular time iron was unknown and after that time it was common. In the Late Bronze Age, although bronze was the common metal for tools and weapons, iron was also known. Because it was difficult to work and obtain, however, it was highly prized. Indeed, it was used in jewelry.

In a famous cuneiform letter, a Hittite king named Hattusilis III (c. 1289–1265 B.C.) replied to a request for iron from someone who may have been the king of Assyria. The Hittite king replied by saying that the iron was not available at present in the amount required, but that it would be produced later. In the meantime, he was sending one dagger-blade of iron as a gesture of good intent. That such a small amount would be adequate to establish good royal intentions indicates how highly valued iron was.

There are several important archeological examples of utensils and jewelry that contained iron as a sign of their value.

At Ugarit, on the Syrian coast, excavators found an axe from the 14th century B.C. with a bronze socket, inlaid with gold; the axe blade is of iron, a worthy complement to the precious socket. In the tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt, who died about 1327 B.C., was a dagger with a magnificent gold hilt and sheath. Its iron blade has not rusted. A few less elaborate weapons and pieces of iron jewelry also survive from this period, and texts refer to more. Lists of treasure drawn up at various cities of the Levant include jewelry of iron and iron daggers, richly mounted like Tutankhamun’s. Even in the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1950–1550 B.C.), cuneiform tablets from Mari in Mesopotamia tell us of iron used in rings and bracelets. In southern Turkey an ivory box was unearthed from a level of the 18th century B.C. decorated with studs of gold, lapis lazuli and iron!

“At a time when iron was hard to obtain, the product of a difficult technique, a bed or a throne decorated with it could be a treasure in a king’s palace, something for visitors to admire.”

So King Og’s enormous Bed of Iron was something like the crown jewels of his kingdom. Iron was not used because of its strength. It was used because of its rarity and value.

Millard explained that this detail actually points to an early authorship of the text - long before the Iron Age. Because if the Torah only dated from the Iron Age (which began around 1,200 BCE) or later - which many Biblical scholars believe to be the case, the detail about the iron is no longer relevant. By then, everyone had iron.

Yet it would make no sense to insert this reference after iron was in common use. On the contrary, its appearance in the text can now be shown by archaeological evidence to be consistent with an early date and inconsistent with a later date.

Indeed, we can now also show from cuneiform texts that such parenthetic remarks are not uncommon and are often an integral part of an original composition. Recording apparently parenthetical details incidental to their story was a way of writing the Israelites shared with other ancient authors—and with modern ones for that matter. Then as now, pieces of local color and unnecessary knowledge can stimulate the interest of readers or hearers; it is unlikely that any greater significance should be attached to their appearance. Simply because they appear to be parenthetical is no basis for concluding that they were inserted by a later editor.

And so, from this smallest of details, Og’s Iron Bed teaches us a great deal. Not only about Og’s size, but perhaps even about the age of the Torah itself.

Want more Talmudology on giants? Click here to read about Goliath, polydactyly and hereditary gigantism.