On today’s page of Talmud we read about Rabbi Yehuda ben Tabbai, who, was rather pleased with himself. In order to make a point of law against the Sadducees, he had sentenced a conspiring false witness to death. Except that he was mistaken. Shimon ben Shetach pointed out that a single conspiring witness cannot be executed. That punishment is reserved when there are two conspiring witnesses.

חגיגה טז, ב

אֵין עֵדִים זוֹמְמִין נֶהֱרָגִין עַד שֶׁיִּזּוֹמּוּ שְׁנֵיהֶם, וְאֵין לוֹקִין עַד שֶׁיִּזּוֹמּוּ שְׁנֵיהֶם, וְאֵין מְשַׁלְּמִין מָמוֹן עַד שֶׁיִּזּוֹמּוּ שְׁנֵיהֶם

Conspiring witnesses are not executed unless they are both found to be conspirators; if only one is found to be a conspirator, he is not executed. And they are not flogged if they are liable to such a penalty, unless they are both found to be conspirators. And if they testified falsely that someone owed money, they do not pay money unless they are both found to be conspirators.

Rabbi Yehuda stood corrected and from then on he would only rule on a matter of law when he was in the presence of Shimon ben Shetach. But what of the innocent person he had executed?

כל יָמָיו שֶׁל יְהוּדָה בֶּן טָבַאי הָיָה מִשְׁתַּטֵּחַ עַל קִבְרוֹ שֶׁל אוֹתוֹ הָרוּג, וְהָיָה קוֹלוֹ נִשְׁמָע. כִּסְבוּרִין הָעָם לוֹמַר שֶׁקּוֹלוֹ שֶׁל הָרוּג הוּא. אָמַר לָהֶם: קוֹלִי הוּא. תֵּדְעוּ, שֶׁלְּמָחָר הוּא מֵת, וְאֵין קוֹלוֹ נִשְׁמָע

All of Yehuda ben Tabbai’s days, he would prostrate himself on the grave of that executed individual, to request forgiveness, and his voice was heard weeping. The people thought that it was the voice of that executed person, rising from his grave. Yehuda ben Tabbai said to them: It is my voice, and you shall know that it is so, for tomorrow, [i.e., sometime in the future,] I will die, and my voice will no longer be heard.

Today, capital punishment is still legal in 55 countries, including Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, and the United States. And so today on Talmudology we will look at the terrible phenomenon of wrongful executions.

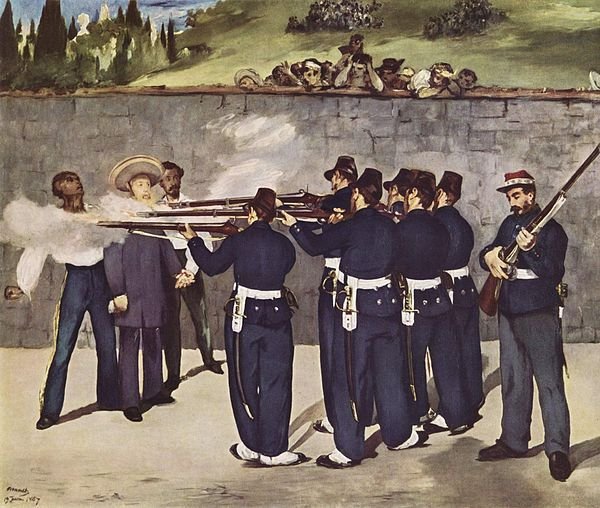

Edouard Manet. The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868–69).

The earliest wrongful executions

Shimon ben Shetach lived around 150 BCE, which is the era in which Rabbi Yehuda’s miscarriage of justice would have taken place. About three hundred years earlier there was another wrongful execution. Or nine, to be more precise. Around the year 440 BCE, nine Hellenotamiai were tried and executed. The Hellenotamiai were a board of ten treasures of the Athenian empire who oversaw the funds and taxes that were paid by members of the empire as tributes. Apparently they miscalculated, and were accused of embezzlement, making them perhaps the earliest white collar criminals in history. Except that they were innocent, as Antiphon recorded.

. . . οἱ Ἑλληνοταμίαι οἱ ὑμέτεροι, ἐκεῖνοι μὲν ἅπαντες ἀπέθανον ὀργῆι μᾶλλον ἢ γνώμηι, πλὴν ἑνός, τὸ δὲ πρᾶγμα ὕστερον καταφανὲς ἐγένετο. τοῦ δ’ ἑνὸς τούτου—Σωσίαν ὄνομά φασιν αὐτῶι εἶναι—κατέγνωστο μὲν ἤδη θάνατος, ἐτεθνήκει δὲ οὔπω· καὶ ἐν τούτωι ἐδηλώθη τῶι τρόπωι ἀπωλώλει τὰ χρήματα, καὶ ὁ ἀνὴρ ἀπήχθη ὑπὸ τοῦ δήμου τοῦ ὑμετέρου παραδεδομένος ἤδη τοῖς ἕνδεκα, οἱ δ’ ἄλλοι ἐτέθνασαν οὐδὲν αἴτιοι ὄντες.

. . . your own Hellênotamiai, they all perished out of anger rather than sound judgment, except one, because the facts of the matter became clear too late. This one—his name, they report, was Sosias—had already been condemned to be executed, but had not yet died. And just in time it was revealed how the money had been lost and the man, even though he had already been delivered to the Eleven, was forcibly rescued by the people, but the others had already died although quite innocent.

Wrongful executions in the early modern era

In 1661 two brothers and their mother were hanged and their bodies placed in iron cages near Campden in England. They had been convicted of the murder of a seventy year old man named William Harrison. But a few years later Harrison showed up, claiming he had been attacked on the night of his disappearance and pressed to serve on a sailing ship. The wrongful execution changed the minds of no-one, and it was later claimed that the mother had been a witch and had orchestrated the events, which were taken to be “signs of Satan's evil designs and of God's overwhelming mercy."

But over the next couple of centuries British judges tried to do better by tightening the requirements for corroboration, especially for the testimony of those who had turned “state’s evidence.” In the 1790s, wrote Bruce Smith, a historian of the law, “British judges increasingly instructed jurors concerning what came to be known as the "beyond-reasonable-doubt" standard of proof-initially, it appears, by instructing jurors to acquit if they had "any rational doubt" as to a defendant's guilt.”

Wrongful executions in TWENTIETH century america

Wrongful executions were also ignored in the United States, as events that could never happen. In 1912 the American Prison Congress published a report claiming to have found not a single case of wrongful execution in American history, though their methodology hardly inspired confidence. They simply asked prison wardens if they had “personal knowledge of the execution of any person on conviction of murder whom you believe, from subsequent developments, to have been innocent?” And there was at least one warden, R. W. McClaughry, of the government prison at Fort Leavenworth, who said: "I know of one or two who may, in my opinion, have been executed wrongfully.”

A couple of decades later, writing in The New Yorker in March 1935, the crime writer Edmund Pearson (1880–1937) was certain that there had been no wrongful executions, at least in the US. Here it is, in the original:

And that’s how things remained until the 1980s, when a philosopher and a sociologist published a paper in the Stanford Law Review in which they identified 350 people who had been wrongfully convicted of capital crimes from 1905 to 1974. Here is a table of their findings:

And here are the executions that were carried out on people that were, according to the authors, innocent of their crimes:

“

Eighteen people have been proven innocent and exonerated by DNA testing in the United States after serving time on death row. They were convicted in 11 states and served a combined 229 years in prison – including 202 years on death row – for crimes they didn’t commit.”

Exonerations after a death sentence today

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, there are now 185 people who have been exonerated after being wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death. And an analysis of theses cases reveals “disturbing patterns of official misconduct and racial bias:”

Nearly 70% of the exonerations involved misconduct by police, prosecutors, or other government officials. 80% of wrongful capital convictions involved some combination of misconduct or perjury/false accusation and more than half involved both. Cases that involved misconduct took longer, on average, to reach exoneration. Misconduct was implicated in all 8 of the exonerations that took more than 30 years and 88% of exonerations that took 21-30 years. Misconduct occurred more often in cases involving Black exonerees (78.8%) than white exonerees (58.2%). Black exonerees spent an average of 4.3 more years waiting for exoneration than white exonerees.

The death penalty inflicted by Rabbi Yehuda ben Tabbai is typical of the errors that involve the death penalty today, in that it involved what we might call “official misconduct.” How hard, really, was it for Rabbi Yehuda to have checked with his colleagues before passing sentence? And it’s not as if Shimon ben Shetach was a bleeding heart liberal. According to the Talmud Yerushalmi, he executed eighty witches in a single day, even though it is forbidden to carry out more than one judicial execution per day. His reasoning was simple: “the times called for it” (אָֽמְרוּ. שְׁמוֹנִם נָשִׁים תָּלָה. וְאֵין דָּנִין שְׁנַיִם בְּיוֹם אֶחָד. אֶלָּא שֶׁהָֽיְתָה הַשָּׁעָה צְרִיכָה לְכָךְ).

Perhaps, fearing such miscarriages of justice, Rabbis Akiva and Tarfon made it clear that they would never vote to convict a person for a capital crime.

משנה מכות 1:10

סַנְהֶדְרִין הַהוֹרֶגֶת אֶחָד בְּשָׁבוּעַ נִקְרֵאת חָבְלָנִית. רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן עֲזַרְיָה אוֹמֵר, אֶחָד לְשִׁבְעִים שָׁנָה. רַבִּי טַרְפוֹן וְרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמְרִים, אִלּוּ הָיִינוּ בַסַּנְהֶדְרִין לֹא נֶהֱרַג אָדָם מֵעוֹלָם. רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר, אַף הֵן מַרְבִּין שׁוֹפְכֵי דָמִים בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל

A Sanhedrin that executes a transgressor once in seven years is characterized as a destructive tribunal. Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya says: This categorization applies to a Sanhedrin that executes a transgressor once in seventy years. Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiva say: If we had been members of the Sanhedrin, we would have conducted trials in a manner whereby no person would have ever been executed…

“No matter how careful courts are, the possibility of perjured testimony, mistaken honest testimony, and human error remain all too real. We have no way of judging how many innocent persons have been executed, but we can be certain that there were some.”