In today’s page of Talmud we read this Mishnah:

מכות כא, א

הַכּוֹתֵב כְּתוֹבֶת קַעֲקַע. כָּתַב וְלֹא קִעֲקַע, קִעֲקַע וְלֹא כָּתַב – אֵינוֹ חַיָּיב, עַד שֶׁיִּכְתּוֹב וִיקַעְקַע (בְּיָדוֹ) [בִּדְיוֹ] וּבִכְחוֹל וּבְכל דָּבָר שֶׁהוּא רוֹשֵׁם. רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן יְהוּדָה מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: אֵינוֹ חַיָּיב עַד שֶׁיִּכְתּוֹב שֵׁם אֶת הַשֵּׁם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וּכְתֹבֶת קַעֲקַע לֹא תִתְּנוּ בָּכֶם אֲנִי ה׳״

From here.

One who imprints a tattoo, by inserting a dye into recesses carved in the skin, is also liable to receive lashes. If one imprinted on the skin with a dye but did not carve the skin, or if one carved the skin but did not imprint the tattoo by adding a dye, he is not liable; he is not liable until he imprints and carves the skin, with ink, or with kohl [keḥol], or with any substance that marks. Rabbi Shimon ben Yehuda says in the name of Rabbi Shimon: He is liable only if he writes the name of the idol there, as it is stated: “And a tattoo inscription you shall not place upon you, I am the Lord” (Leviticus 19:28).

As Rashi notes, the Talmud explains that the prohibition is to tattoo the name of an idol onto the skin:

את השם - מפרש בגמרא דשם עבודת כוכבים קאמר

The Rambam includes this prohibition in his Mishnah Torah:

משנה תורה, הלכות עבודה זרה וחוקות הגויים י״ב:י״א

כְּתֹבֶת קַעֲקַע הָאֲמוּרָה בַּתּוֹרָה הוּא שֶׁיִּשְׂרֹט עַל בְּשָׂרוֹ וִימַלֵּא מְקוֹם הַשְּׂרִיטָה כָּחל אוֹ דְּיוֹ אוֹ שְׁאָר צִבְעוֹנִים הָרוֹשְׁמִים. וְזֶה הָיָה מִנְהַג הָעַכּוּ"ם שֶׁרוֹשְׁמִין עַצְמָן לַעֲבוֹדַת כּוֹכָבִים כְּלוֹמַר שֶׁהוּא עֶבֶד מָכוּר לָהּ וּמֻרְשָׁם לַעֲבוֹדָתָהּ. וּמֵעֵת שֶׁיִּרְשֹׁם בְּאֶחָד מִדְּבָרִים הָרוֹשְׁמִין אַחַר שֶׁיִּשְׂרֹט בְּאֵי זֶה מָקוֹם מִן הַגּוּף בֵּין אִישׁ בֵּין אִשָּׁה לוֹקֶה. כָּתַב וְלֹא רָשַׁם בְּצֶבַע אוֹ שֶׁרָשַׁם בְּצֶבַע וְלֹא כָּתַב בִּשְׂרִיטָה פָּטוּר עַד שֶׁיִּכְתֹּב וִיקַעֲקֵעַ שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (ויקרא יט כח) "וּכְתֹבֶת קַעֲקַע". בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים בְּכוֹתֵב אֲבָל זֶה שֶׁכָּתְבוּ בִּבְשָׂרוֹ וְקִעְקְעוּ בּוֹ אֵינוֹ חַיָּב אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן סִיֵּעַ כְּדֵי שֶׁיַּעֲשֶׂה מַעֲשֶׂה. אֲבָל אִם לֹא עָשָׂה כְּלוּם אֵינוֹ לוֹקֶה

The tattooing which the Torah forbids involves making a cut in one's flesh and filling the slit with eye-color, ink, or with any other dye that leaves an imprint. This was the custom of the idolaters, who would make marks on their bodies for the sake of their idols, as if to say that they are like servants sold to the idol and designated for its service…

If a person wrote and did not dye, or dyed without writing by cutting [into his flesh], he is not liable. [Punishment is administered] only when he writes and dyes, as [Leviticus 19:28] states: "[Do not make] a dyed inscription [on yourselves]…

Of course we do not have any images that show how these tattoos appeared in Talmudic times, but we do have examples of these kinds of images in our own culture. Here are a few:

Anubis

Anubis is the Egyptian god of funerary rites and a guide to the underworld. In ancient Egypt he is displayed as having the head of a jackal and the body of a man. Like the image on the left, shown from the Tomb of Horemheb; 1323-1295 BCE, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Anubis, from the Tomb of Horemheb; 1323-1295 BCE, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

And here is how he is depicted on a contemporary tattoo:

From here.

Sekhmet

Sekhmet, the daughter of sun god Ra, is an Egyptian goddess who could breathe fire, cause plagues (which were described as being her servants or messengers), and, if you were lucky, ward off disease and heal the sick. Here she is depicted on the Temple of Kom Ombo in Egypt, from around 180 BCE:

From here.

And here she is, tattooed:

From here.

Shiva

Shiva is the Hindu god of destruction and regeneration. Here he is in the 6th century Elephanta caves in Maharashtra, India

Shiva, carved into rock and about 20 feet heigh. From here.

Shiva is a popular god for tattoo artists (and it is they who have the injunction mentioned in the Mishnah. The person being tattooed does not violate any prohibition according to the Rambam, unless she helps the one drawing the tattoo - וְקִעְקְעוּ בּוֹ אֵינוֹ חַיָּב אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן סִיֵּעַ כְּדֵי שֶׁיַּעֲשֶׂה מַעֲשֶׂה).

Shiva

Another Shiva, created by this tattoo parlor.

What about Tattooing the name of our God?

On a delightful sunny day in August 2012 I was enjoying a refreshing Coke with my family at a quiet coffee shop in Toledo, Spain, where we were on vacation. Near us was man enjoying his own refreshment, and I could not help notice the tattoo on his left arm.

And then I noticed the tattoo on his right arm. Eloheynu - “Our God.”

Unfortunately there was a language barrier that prevented us from having what would have been, I am sure, a most interesting little chat. I might even have shared with this nice man with a gentle smile the ruling from the Talmud in Yoma:

יומא ח, א

הֲרֵי שֶׁהָיָה שֵׁם כָּתוּב עַל בְּשָׂרוֹ — הֲרֵי זֶה לֹא יִרְחַץ וְלֹא יָסוּךְ וְלֹא יַעֲמוֹד בִּמְקוֹם הַטִּנּוֹפֶת. נִזְדַּמְּנָה לוֹ טְבִילָה שֶׁל מִצְוָה — כּוֹרֵךְ עָלָיו גֶּמִי וְטוֹבֵל. רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: יוֹרֵד וְטוֹבֵל כְּדַרְכּוֹ, וּבִלְבַד שֶׁלֹּא יְשַׁפְשֵׁף

It was taught in a baraita: With regard to one who had a sacred name of God written on his flesh, he may neither bathe, nor smear oil on his flesh, nor stand in a place of filth. If an immersion by means of which he fulfills a mitzva happened to present itself to him, he wraps a reed over God’s name and then descends and immerses, allowing the water to penetrate so that there will be no interposition between him and the water. Rabbi Yossi says: Actually, he descends and immerses in his usual manner, and he need not wrap a reed over the name, provided that he does not rub the spot and erase the name.

Rabbi Yossi implies that the name of God was literally written on the skin, rather than tattooed. And this is how Rashi explains the Talmud:

לא ירחץ – שלא ימחקנו. ואזהרה למוחק את השם "ואבדתם את השם" וסמיך ליה "לא תעשון ן וגו'

He may not bathe - to prevent it from being erased…

This was codified by Maimonides in his Mishneh Torah:

רמב’ם משנה תורה הל׳ יסידי התורה 6:6

וְכֵן אִם הָיָה שֵׁם כָּתוּב עַל בְּשָׂרוֹ הֲרֵי זֶה לֹא יִרְחַץ וְלֹא יָסוּךְ וְלֹא יַעֲמֹד בִּמְקוֹם הַטִּנֹּפֶת. נִזְדַּמְּנָה לוֹ טְבִילָה שֶׁל מִצְוָה כּוֹרֵךְ עָלָיו גֶּמִי וְטוֹבֵל. וְאִם לֹא מָצָא גֶּמִי מְסַבֵּב בִּבְגָדָיו וְלֹא יְהַדֵּק כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא יָחֹץ. שֶׁלֹּא אָמְרוּ לִכְרֹךְ עָלָיו אֶלָּא מִפְּנֵי שֶׁאָסוּר לַעֲמֹד בִּפְנֵי הַשֵּׁם כְּשֶׁהוּא עָרֹם

…If one had a Name written upon his flesh, he shall not wash, anoint himself or remain in unclean places; if he must undergo a mandatory immersion, he shall cover it with a leaf or, when no leaf is to be found, with part of his garments, yet must he not fasten it lest it be obstructive to the immersion, because the only reason it was said to cover the tattoo is because it is forbidden to remain naked in the Presence of the God’s Name.

But it is also possible that the Talmud is referring to a more extreme form of writing on the skin: tattooing. On that sunny day in Spain I was surprised to find that God’s Hebrew name was something people would tattoo on themselves. But I should not have been. As the Talmud in Yoma makes clear, people have been writing God’s name on themselves for a long time. And so here, for your viewing delight are some other examples of this phenomenon.

Let’s start with one that is not the name of God, but a common word associated with good luck. It is the Hebrew word חי chai, meaning life.

From here

Ok, the next one doesn’t count. It is a poor transliteration of the four letter name of God י–ה–ו–ה written in English as “Yahweh.”

From here.

But this one is unmistakably God’s ineffable name. Or it will be once the thing is finished and someone colors in the letters.

From here.

Not sure what is going on here. This Hebrew tattoo means “But God [Elohim].” But God what?

From here.

Here is another one using the word Elohim. (This image was rotated 90 degrees to enable you to read the words easily.)

It is a quote from Psalms 46:11 הַרְפּ֣וּ וּ֭דְעוּ כִּי־אָנֹכִ֣י אֱלֹהִ֑ים אָר֥וּם בַּ֝גּוֹיִ֗ם אָר֥וּם בָּאָֽרֶץ׃ “Desist! Realize that I am God! I dominate the nations; I dominate the earth.”

From here.

Same verse. Only smaller. And this one has the advantage that when immersing in a Mikveh [ritual bath], it may easily be covered with a sock.

From here.

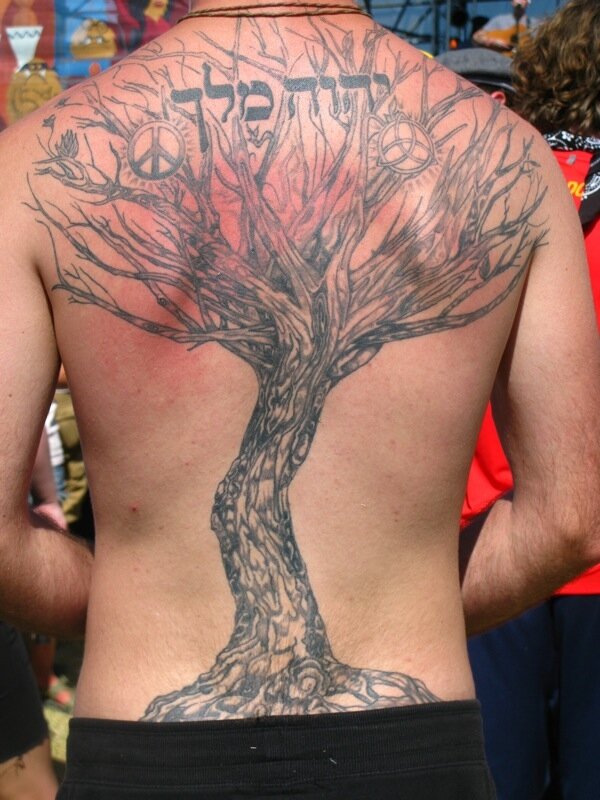

Next, “God is King.” Possibly the winner in the category “Largest Hebrew Name-of God Tattoo.”

From here.

Another example of the four letter name of God tattooed. Twice. And another winner, this time in the category of “I forgot my prayer book - what are the words?” It is Psalm 23. All of it.

From here.

The Jewish Prohibition against Tattooing

Jews are forbidden to get a tattoo. The origin of this prohibition is found in the Torah (Lev. 19:28)

וְשֶׂ֣רֶט לָנֶ֗פֶשׁ לֹ֤א תִתְּנוּ֙ בִּבְשַׂרְכֶ֔ם וּכְתֹ֣בֶת קַֽעֲקַ֔ע לֹ֥א תִתְּנ֖וּ בָּכֶ֑ם אֲנִ֖י יְהוָֽה׃

You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead, or incise any marks on yourselves: I am the Lord.

Maimonides is clear:

משנה תורה, מצוות לא תעשה מ״א

שלא לכתוב בגוף כעובדי עבודה זרה, שנאמר "וכתובת קעקע, לא תיתנו בכם" (ויקרא יט,כח)

Mishneh Torah, Negative Mitzvot 41

Not to tattoo the body, like the idolaters, as it is said, “…. nor shall ye print any marks upon you” (Lev. 19:28).

And here is the Sefer HaChinuch, an important anonymous work written in Spain sometime in the 13th-century. It details the 613 commandments and explains the reasons behind them.

Sefer HaChinukh 253:1

That we not imprint an imprinted tattoo into our flesh:

To not imprint an imprinted tattoo into our flesh, as it is stated (Leviticus 19:28), "and an imprinted tattoo you shall not put into your flesh." And the content is like that which the Yishmaelites do today, as they imprint an imprint that is inscribed and stuck into their flesh, such that it is never erased. And the liability is only with an imprint that is inscribed and impressed with ink or blue dye or with other colors that make an impression. And so did they say in Makkot 21a, "[If] he tattooed, but did not imprint" - meaning to say, he did not make an impression with color - "[if] he imprinted, but did not tattoo" - meaning to say that he did make an impression [on] his flesh with a color, but he did not make a marking in his flesh - " he is not liable, until he imprints, and tattoos with ink, or with blue dye or with anything that makes an impression."

Still, the Torah ruling is specific: “You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead.” But what if the gashes are not made “for the dead”? As a 2008 article from the New York Times made clear, many contemporary Jews grapple with the prohibition.

Andy Abrams, a filmmaker, has spent five years making a documentary called “Tattoo Jew.” In his interviews with dozens of Jews with body art, he’s noticed the prevalence of Jewish-themed tattoos from Stars of David to elaborate Holocaust memorials, surprising since one reason Jewish culture opposes tattoos is that Jews were involuntarily marked in concentration camps.

And that thing you’ve heard that a Jew with a tattoo cannot be buried in a Jewish cemetery? Nonsense. An urban legend. As The New York Times noted:

But the edict [against a Jew with a tattoo being buried in a Jewish cemetery] isn’t true. The eight rabbinical scholars interviewed for this article, from institutions like the Jewish Theological Seminary and Yeshiva University, said it’s an urban legend, most likely started because a specific cemetery had a policy against tattoos. Jewish parents and grandparents picked up on it and over time, their distaste for tattoos was presented as scriptural doctrine.

What is remarkable about the Talmud in Yoma is that there is no comment made about how a Jewish person could ever be in the position of having to cover a tattoo. It just took it for granted that such a case could occur. Perhaps the person transgressed the prohibition, and now want to bathe in the cleansing waters of the ritual mikveh.

“It’s difficult to know exactly how many young Jews are being tattooed, because no organization tracks these numbers. But a pro-tattoo community is emerging online. Christopher Stedman, a 23-year-old student in Rohnert Park, Calif., started a MySpace group called “Jews with Tattoos” in 2004, after noticing more Jewish friends being tattooed. The group now has 839 members.”

Why Tattoo?

In his fascinating book Science Ink: Tattoos of the Science Obsessed, Carl Zimmer wrote that scientists get tattoos (and many of them do, judging from this book) “in order to mark themselves with an aspect of the world that has marked them deeply within. It is not simply the thing in the tattoo that matters…tattoos are a tribal marking: they display a membership with the universe itself.” And for those with the proclivity, what better way is there to remember the God (or gods) who got the whole thing rolling than by tattooing of his name. Just be sure that you choose the right god.

Two beautiful equations on the arms of Adam Simpson, who worked at the National Center for Computational Sciences. “I got the tattoos because it’s amazing to me how just a few characters can impact the world so much, and I want others to know that.” From Carl Zimmer, Science Ink; Tattoos of the Science Obsessed. New York. Sterling 2011. p28.