Bertrand RusselL’s Teapot

The great British philosopher Bertrand Russell (d.1970,) was also a great British atheist, who tired of some of the claims made in support of a belief in God. In 1952 he wrote the following:

Many orthodox people speak as though it were the business of sceptics to disprove received dogmas rather than of dogmatists to prove them. This is, of course, a mistake. If I were to suggest that between the Earth and Mars there is a china teapot revolving about the sun in an elliptical orbit, nobody would be able to disprove my assertion provided I were careful to add that the teapot is too small to be revealed even by our most powerful telescopes. But if I were to go on to say that, since my assertion cannot be disproved, it is intolerable presumption on the part of human reason to doubt it, I should rightly be thought to be talking nonsense. If, however, the existence of such a teapot were affirmed in ancient books, taught as the sacred truth every Sunday, and instilled into the minds of children at school, hesitation to believe in its existence would become a mark of eccentricity and entitle the doubter to the attentions of the psychiatrist in an enlightened age or of the Inquisitor in an earlier time.

Whether or not one believes that Russel’s teapot is a reasonable analog to theistic belief, it is a reminder that when making an empirically unfalsifiable claim, the burden of proof does not lie on others to disprove it. We have no reason to believe the claim unless it has been proven by those who asserted its truth. It is worth remembering Russel’s teapot when considering some claims made in the Talmud; those which are not plausible must be considered to be just that, regardless of whether the claim has been empirically disproven.

Rather unexpectedly, one noted scholar seems to have taken up Russel’s Teapot challenge, and set out to explain that the Barrel Test as described by Rabban Gamliel, was a reliable test of a woman’s virginity.

Rabbi Mordechai Halperin AND The Barrel TesT

Rabbi Mordechai Halperin is an accomplished and highly respected physician in Jerusalem. Some of his books adorn the Talmudology library. He was the Chief Ethics officer at the Israeli Ministry of Health, and the editor of Assiah, the Journal of Jewish Ethics and Halacha. And Rabbi Halperin believes that the test has a basis in fact. Here are the steps in his argument, (and you can read the original here):

1) Some foods, like garlic, are broken down into substances that are absorbed into the bloodstream. These may later be expelled from the blood in the lungs, and may be smelled on the breath.

2) Many medicines and food substances can be directly absorbed from the mucosa. So, for example, some drugs are placed under the tongue, where they may directly enter the blood stream by crossing into the tiny blood vessels that line the mucosal surface. Alcohol can not only be absorbed into the blood by ingestion into the stomach. It may also cross directly, via a mucosal surface. The vagina is a mucosal surface,

3) The difference between a virgin and non-virgin is in the tone of the vaginal passage.

As a result, Rabbi Halperin claims that a non-virgin has a lower vaginal tone and that the vaginal mucosa will absorb more alcohol when placed over a wine barrel when compared with a woman who is a virgin. And so the blood alcohol concentration will be higher in the former than in the latter. This will be detectable by the smelling the breath of the woman. QED.

Before we go on, an apology

OK, before we go on any further, I want to apologize to the many woman (and men) who might feel outraged at this discussion. I know it reminds us of a time when, in Judaism (and in Christianity too) virginity was the most important of qualities that a bride could have. (For more on that, see yesterday’s post.) In many cultures it still is, and women who are suspected of not being virgins on the night of their wedding sometimes face violence and even murder. Here is Michael Rosenberg’s take, from his terrific (and expensive) book Signs of Virginity: Testing Virgins and Making Men in Late Antiquity (p.139):

We need not - and should not - ignore the grotesque and degrading image of setting a woman up on a barrel to test her virginity to see that Rabban Gamliel b. Rabbi’s action is meant to bear the trappings of an objective process….

Critical to understanding the story is reading it in the light of its parallel in Tractate Yevamot of the Bavli. There, the Babylonian sage Rav Kahana suggests the barrel method for determining virginity. The striking difference between the appearance of the barrel test in bYev60b and its appearance here is that the version in Yevamot lacks the use of two maidservants to test out the method. There, Rav Kahana simply explains what one should do. In our passage [in Ketuvot] , this plot device highlights the “objectivity” of what Rabban Gamliel b. Rabbi is doing; the editor(s) of the story depict Rabban Gamliel b. Rabbi’s experiment as rigorous and /or objective. In the language of the modern scientific method: he tests out a hypothesis using controlled variables, and when that hypothesis is confirmed, he then makes use of it to determine the answer to an unknown question.

So, we must continue, in the name of science. The problem with Rabbi Halperin’s suggestion is that while the individual steps might be correct, they do not in any way lead to his conclusion.

How Scientific was Rabban Gamliel’s Methodology?

Rosenberg points out some of the features that Rabban Gamliel’s test has in common with “the language of the modern scientific method.” But to be clear, there was nothing scientific about it, at least in so far as we use the word today. For this, Rabban Gamliel cannot be blamed. He lived about 1,300 years before the birth of modern science, and it is silly of us to think he should have been conducting his test along the same lines that we conduct scientific tests today. Still, it is worth thinking about his methods through the lens of modern science. We will quickly see that the test, at least as described in Ketuvot, was far from scientific.

Rabban Gamliel selected two women to take part in the calibration phase. They were “maidservants” a position that might mean anything from an employee to a slave. Were they coerced, or did they volunteer? If the former, the study was unethical.

What were their ages, had they borne the same number of children, and where in their menstrual cycles were they? The latter is especially important since it affects the lining of the vagina and uterus (more on this below).

Was the test blinded? Were the barrels identical? Was the same wine used in each? When calibrating his nose, how often did he smell? How long did each woman sit over the wine?

In the actual test, did the bride seat herself for the same length of time as the women in the calibration phase? Was the same barrel used? Was it the same wine? Was the woman in the same part of her menstrual cycle as the women in the calibration phase?

Unless we know the answers to these questions (and many more), Rabban Gamliel’s test, interesting as it is, remains a far cry from anything that would pass as modern science. While it was published in the Talmud, it would not make it into any peer reviewed journal today. (Well, OK, maybe this one.)

With the possible exception of Rabbi Shimon ben Chalafta, the rabbis of the Talmud weren’t scientists. They were rabbis.

How good is the nose at detecting blood alcohol Levels?

Most of us are able to smell alcohol on the breath of a person who has consumed it. (Yes, I know that actually, pure alcohol has very little or no odor [think of vodka] and that the smell is really from the tannins, hops and other substances that make up the wine or beer or whatever. But let’s keep going.) How sensitive are our noses? Not very, it turns out. In one study, twenty “experienced” police officers were asked to smell the breath of fourteen volunteers who had been drinking, and whose precise blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) were known. How did the officers do?

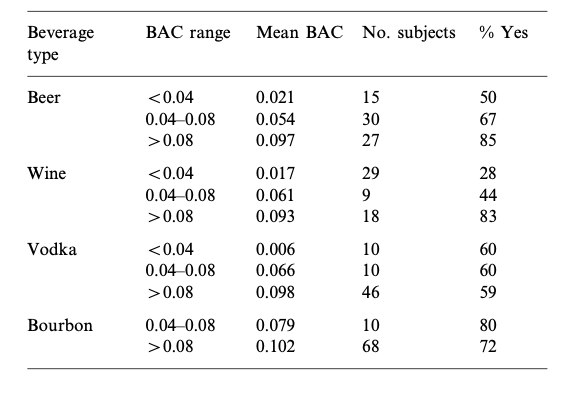

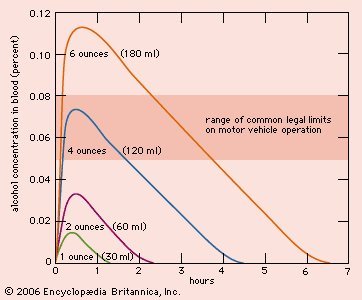

Well, it depends on the BAC. Consider a BAC of 0.08%, the legal limit for driving in many places. To get that, most people would need to have four or five drinks. At that high level, the odor was correctly identified 80% of the time. At levels less that that, the alcohol could not usually be detected.