The Mishna on yesterday’s daf, Bava Basra 20b, teaches what are reasonable and unreasonable uses of one’s home. A neighbor may object to you running your store in a common courtyard, because of the noise generated. But she may not object to your running a school:

בבא בתרא כ, ב

חֲנוּת שֶׁבְּחָצֵר – יָכוֹל לִמְחוֹת בְּיָדוֹ וְלוֹמַר לוֹ: אֵינִי יָכוֹל לִישַׁן מִקּוֹל הַנִּכְנָסִין וּמִקּוֹל הַיּוֹצְאִין…וְלֹא מִקּוֹל הַתִּינוֹקוֹת

MISHNA: If a resident wants to open a store in his courtyard, his neighbor can protest to prevent him from doing so and say to him: I am unable to sleep due to the sound of people entering the store and the sound of people exiting….nor can he say: I cannot sleep due to the sound of the children.

On today’s daf, the Talmud teaches that this ruling applied from the time of the ruling of Yehoshua ben Gamla and onwards:

בבא בתרא כא, א

דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: בְּרַם, זָכוּר אוֹתוֹ הָאִישׁ לַטּוֹב – וִיהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן גַּמְלָא שְׁמוֹ, שֶׁאִלְמָלֵא הוּא, נִשְׁתַּכַּח תּוֹרָה מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל. שֶׁבִּתְחִלָּה, מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ אָב – מְלַמְּדוֹ תּוֹרָה, מִי שֶׁאֵין לוֹ אָב – לֹא הָיָה לָמֵד תּוֹרָה. מַאי דְּרוּשׁ? ״וְלִמַּדְתֶּם אֹתָם״ – וְלִמַּדְתֶּם אַתֶּם

הִתְקִינוּ שֶׁיְּהוּ מוֹשִׁיבִין מְלַמְּדֵי תִינוֹקוֹת בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם. מַאי דְּרוּשׁ? ״כִּי מִצִּיּוֹן תֵּצֵא תוֹרָה״. וַעֲדַיִין מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ אָב – הָיָה מַעֲלוֹ וּמְלַמְּדוֹ, מִי שֶׁאֵין לוֹ אָב – לֹא הָיָה עוֹלֶה וְלָמֵד. הִתְקִינוּ שֶׁיְּהוּ מוֹשִׁיבִין בְּכל פֶּלֶךְ וּפֶלֶךְ. וּמַכְנִיסִין אוֹתָן כְּבֶן שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה כְּבֶן שְׁבַע עֶשְׂרֵה

וּמִי שֶׁהָיָה רַבּוֹ כּוֹעֵס עָלָיו – מְבַעֵיט בּוֹ וְיֹצֵא. עַד שֶׁבָּא יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן גַּמְלָא וְתִיקֵּן, שֶׁיְּהוּ מוֹשִׁיבִין מְלַמְּדֵי תִינוֹקוֹת בְּכל מְדִינָה וּמְדִינָה וּבְכל עִיר וָעִיר, וּמַכְנִיסִין אוֹתָן כְּבֶן שֵׁשׁ כְּבֶן שֶׁבַע

What was this ordinance? As Rav Yehuda says that Rav says: Truly, that man is remembered for the good, and his name is Yehoshua ben Gamla. If not for him the Torah would have been forgotten from the Jewish people. Initially, whoever had a father would have his father teach him Torah, and whoever did not have a father would not learn Torah at all.

The Gemara explains: What verse did they interpret homiletically that allowed them to conduct themselves in this manner? They interpreted the verse that states: “And you shall teach them [otam] to your sons” (Deuteronomy 11:19), to mean: And you yourselves [atem] shall teach, i.e., you fathers shall teach your sons.

When the Sages saw that not everyone was capable of teaching their children and Torah study was declining, they instituted an ordinance that teachers of children should be established in Jerusalem. The Gemara explains: What verse did they interpret homiletically that enabled them to do this? They interpreted the verse: “For Torah emerges from Zion” (Isaiah 2:3). But still, whoever had a father, his father ascended with him to Jerusalem and had him taught, but whoever did not have a father, he did not ascend and learn. Therefore, the Sages instituted an ordinance that teachers of children should be established in one city in each and every region. And they brought the students in at the age of sixteen and at the age of seventeen.

But as the students were old and had not yet had any formal education, a student whose teacher grew angry at him would rebel against him and leave. It was impossible to hold the youths there against their will. This state of affairs continued until Yehoshua ben Gamla came and instituted an ordinance that teachers of children should be established in each and every province and in each and every town, and they would bring the children in to learn at the age of six and at the age of seven.

It is not very often that I read a book that changes everything about what I thought I knew. But a year ago I read just such a book. It is The Chosen Few, by two economists, Maristella Botticini and Zvi Eckstein. I cannot recommend it highly enough, and it explains why today’s daf contains the most important ruling in the Talmud.

“The ability to read and write contracts, business letters and account books using a common alphabet gave the Jews a comparative advantage over other people. The Jews also developed a uniform code of law (the Talmud) and a set of institutions, networking and arbitrage across distant locations. High levels of literacy and the existence of contract-enforcing institutions became the levers of the Jewish people.”

This book was written to answer one specific question – though in doing so it revealed a remarkable story. Why was it that the worldwide Jewish population decreased from about three million at the time of the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, to barely one million by 1490? It wasn’t just wars, famine or pandemics, because the world population increased over that same period, from about 55 to 87 million.

Jewish and total population, c. 65 CE, 650, 1170, and 1490 (millions). Source: Authors’ estimates, explained in appendix. From Botticini M. and Eckstein Z. The Chosen Few. How Jewish Education Shaped Jewish History 70-1492. Princeton University Press 2012. p18.

How Yehoshua ben Gamla Changed the Jewish trajectory

Here is what the authors believe happened.

Yehoshua ben Gamla was a High Priest in the Second Temple and died during the first Jewish-Roman war in about 64-65 CE. He issued a decree that all Jewish fathers were required to send their sons (but not their daughters, sorry,) from the age of six or seven to school. There, they would learn to read and write and study Torah. “Throughout the first millennium” wrote Botticini and Eckstein, “no people other than the Jews had a norm requiring fathers to educate their sons.” Then came this critical change in Jewish society:

With the destruction of the Second Temple, the Jewish religion permanently lost one of its two pillars (the Temple) and set out on a unique trajectory. Scholars and rabbis, the new religious leaders in the aftermath of the first Jewish-Roman war, replaced temple service and ritual sacrifices with the study of the Torah in the synagogue, the new focal institution of Judaism. Its core function was to provide religious instruction to both children and adults. Being a devout Jew became identified with reading and studying the Torah and sending one’s children to school to learn to do so. During the next century, the rabbis and scholars in the academies in the Galilee interpreted the Written Torah, discussed religious norms as well as social and economic matters pertaining to daily life, and organized the body of Oral Law accumulated through the centuries. In about 200, Rabbi Judah haNasi completed this work by redacting the six volumes of the Mishna, which with its subsequent development, the Talmud, became the canon of law for the whole of world Jewry. Under the leadership of the scholars in the academies, illiterate people came to be considered outcasts.

Why Jews Stopped Farming

Next, the authors address the implications of this new religious norm for the behavior of Jews in the first half of the new millennium. Until this time, the most common occupation was as farmers, but now each family unit had to make a stark choice. Do they invest in their sons’ literacy, and also remain within the network of the normative Jewish community, or finding them too costly, do they convert to other religions?

“If the economy remains mainly agrarian, literate people cannot find urban and skilled occupations in which their investment in literacy and education yields positive economic returns. As a result the Jewish population keeps shrinking and becoming more literate. In the long run, Judaism cannot survive in a subsistence farming economy because of the process of conversions.”

If you wished to remain within the fold of rabbinic Judaism, then you had to send your sons to school. This was the edict of Yehoshua ben Gamla, and it had to be followed. But this pulled them out of the farming workforce, which would mean an end to the family farm. But if you wished to remain a farmer, then you kept your sons (and daughters) close by to help on the farm. However, this put you outside of the new normative Jewish practice of sending sons to school. Pretty soon, those who remained farmers were outside the pale of normative Jewish practice, and would have converted to Christianity (or, later Islam). And that explains the rapid drop in the Jewish population.

With his income, the Jewish farmer buys food and clothing for his family and pays taxes. If he decides to send his sons to school, he has to incur the associated costs. He has to pay for books and contribute to both the teacher’s salary and the maintenance of the synagogue where the school activities are typically held. In small communities, these expenses may represent a heavy burden on the household head. Given heterogeneity in individuals’ abilities and temperaments, the cost of educating a child may decrease with his ability and diligence. The costs of educating one’s son also include the forgone earnings the child could have earned by working on the farm rather than attending school—what economists refer to as “opportunity cost.” Even if education is free (because, for example, the state provides books and pays all tuition), the opportunity cost of going to school makes educating children a burden for farmers, especially poor and middle-income ones. (Even today, many farmers in developing countries that provide free universal primary education keep their children out of school so that they can work on the farm.)

Next let us consider the benefits and the costs associated with the second choice the Jewish farmer has to make: whether to remain a Jew or to opt for another religion. The Jewish farmer can avoid following the rules set by Judaism, including the one requiring him to educate his sons, by converting to another religion. Doing so would free him of the costs of educating his children or suffering the social penalty inflicted on the illiterate. A Jew who converts, however, may suffer psychological or monetary costs, including losing the support of his Jewish friends and relatives. We call the costs associated with converting to another religion the “costs of conversion.”

Religious affiliation typically requires some costly signal of belonging to a club or network; different religions may require their members to follow different rituals and adhere to different norms as a way to signal their membership in the club. Investing in literacy and education, as Judaism requires, is a very costly signal for individuals and households living in farming economies in which there are no economic returns to literacy. As we show, the decisions to invest in a son’s literacy and to remain or become a member of a religious group are related.

So, more Jews became urban merchants, and fewer became farmers. There were now fewer Jews to be sure, but they had their educated sons now had the ability to pivot from farming to trading.

“The literacy of the Jewish people, couples with a set of contract enforcement institutions developed during the five centuries after the destruction of the Second Temple gave Jews a comparative advantage in occupations such as crafts, trade and money lending, occupations that benefited from literacy, contract-enforcement mechanisms, and networking. Once the Jews were engaged in these occupations they rarely converted, which is consistent with the fact that the Jewish population grew slightly from the seventh to the twelfth century.”

Why Jews Became MoneyLenders

Sometime during my education I was told that Jews turned to moneylending because they were prohibited from owning land, and because they were expelled from countries and communities so often that they were forced to enter a trade that was portable. I am sure that you heard this explanation too. But it is wrong.

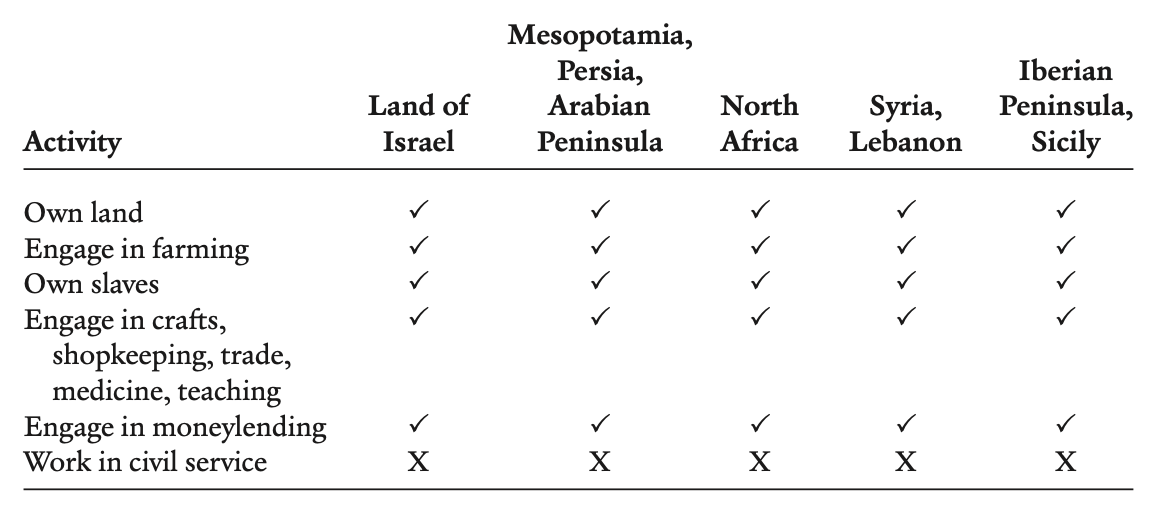

First, Jews were never prohibited from owning land in either the Roman or the Persian empires. In fact, they were not prohibited from any economic activities, then, or later in the Byzantine Empire (350-1250 CE.) or the Muslim Caliphates (650-1250 CE.). And what about Christian Europe?

No restrictions were imposed on the Jewish artisans, shopkeepers, traders, moneylenders, scholars, and physicians who migrated to and within Christian Europe during the early Middle Ages. Many charters issued in the early medieval period (the mid-ninth through the thirteenth century) indicate that rulers invited Jews to settle in their lands in order to spur the development of crafts and trade…

Economic Activities Open and Closed to Jews in the Muslim Caliphates, by Area, 650–1250. From Botticini M. and Eckstein Z. The Chosen Few. How Jewish Education Shaped Jewish History 70-1492. p57.

“The decision of the Jews to invest in literacy and education (first to sixth century) came centuries before their worldwide migrations (ninth century onwards). The direction of causality thus runs from investment in literacy and human capital to voluntarily giving up investing in land and being farmers to entertaining urban occupations and becoming mobile and migrating - not the other way round.”

An Economic View of Jewish Identity

Both Botticini and Eckstein are economists, and note that “economists assume that when making choices, individuals compare the benefits and the costs of the alternatives with the goal of selecting the option that yields the greatest utility.”

A Jewish farmer (that is, a farmer who identifies himself with Judaism) living in a village in the Galilee circa 200 had to make two key choices. First, he had to decide whether to send his sons to work or to school (synagogue) to learn to read and study the Torah. Second, he had to choose whether to continue belonging to Judaism or to convert and become a Samaritan, a Christian, or a pagan.

Their book analyzes these and other choices, noting that literacy did not make a farmer more productive or enable him to earn more.

Moreover, the rural economies of the first half of the first millenium there were very few opportunities for literate people to enter crafts and trades. “Investment” in children’s literacy and education thus represented a burden with no economic returns for almost all households whose incomes came from agriculture.

Of course, the ruling of Yehoshua ben Gamla would not have had much effect without an educational infrastructure. Over the first few centuries after the destruction of the Second Temple, several further edicts provided (some described on today’s page of Talmud) levied a communal tax to pay for the teacher’s salary, and introduced competitive competition between teachers as a way of raising standards. A small number of Jewish farmers made the financial sacrifice to obey the religious norm sanctioned by the Pharasaic leadership. Over time, there were fewer and fewer Jewish farmers, and more and more Jewish merchants.

Literacy—and hence, the ability to read and write contracts, deeds, and letters - greatly enhanced the establishment of business partnerships among traders, as treasures from the Cairo Geniza have shown. but one example, a letter was sent around 1040 by the Tunisian-Jewish trader Yahyā, son of Mūsā, to his former apprentice and current partner, living in Egypt:

You wrote about the loss of part of the copper—may God compensate me and you, then—about the blessed profit made from the antimony and, finally, about the lac and the odorous wood which you bought and loaded on Mi‘dād and ‘Abūr. (You mentioned) that the bale on Mi‘dād was unloaded afterward; I have no doubt that the other will also be unloaded. I hope, however, that there will be traffic on the Barqa route. Therefore, repack the bales into camel-loads— half their original size—and send them via Barqa. Perhaps I shall get a good price for them and acquire antimony with it this winter. For, dear brother, if the merchandise remains in Alexandria year after year, we shall make no profit.

Only small quantities of odorous wood are to be had here, and it is much in demand. Again, do not be remiss, but make an effort and send the goods on the Barqa route—may God inspire you and me and all Israel to do the right thing.

Of course there is more to the story, and The Chosen Few includes important data that addresses how the Jews became educated in the middle ages, and built vast trading networks across Europe and the Middle East. It is a fascinating read. Some two thousand years after his ruling that is recorded on today’s page of Talmud, Jews continue to benefit from the edict of Yehoshua ben Gamla.

“The four centuries spanning from the redaction of the Mishna circa 200 to the rise of Islam in the mid-seventh century witnessed the implementation of Joshua ben Gamla’s ruling and the establishment of a system of universal primary education centered on the synagogue. This sweeping change completely transformed Judaism into a religion centered on reading, studying and implementing the rules of the Torah and the Talmud. A Jewish farmer going on pilgrimage to and performing ritual sacrifices in the Temple in Jerusalem was the icon of Judaism until 70 CE. In the early seventh century, the emblem of world Jewry was a Jewish farmer reading and studying the Torah in a synagogue, and sending his sons to school or the synagogue to learn to do so.”