As the Talmud addresses the responsibility for the injuries of one cow caused by another, today we will look at the dangers of praying too close to these usually gentle animals. Back in Masechet Berachot, there is a discussion of the circumstances under which a person may interrupt her prayers because of a threatened physical danger. Getting too close to snakes is not a good idea, but cows are a problem too.

ברכות לג, א

אָמַר רַבִּי יִצְחָק: רָאָה שְׁווֹרִים — פּוֹסֵק. דְּתָנֵי רַב הוֹשַׁעְיָה: מַרְחִיקִין מִשּׁוֹר תָּם — חֲמִשִּׁים אַמָּה, וּמִשּׁוֹר מוּעָד — כִּמְלוֹא עֵינָיו

Rabbi Yitzchak said: One who saw oxen coming toward him, he interrupts his prayer, as Rav Hoshaya taught: One distances himself fifty cubits from an innocuous ox [shor tam], an ox with no history of causing damage with the intent to injure, and from a forewarned ox [shor muad], an ox whose owner was forewarned because his ox has gored three times already, one distances himself until it is beyond eyeshot.

So today we will discuss injuries from oxen and cows. But first, just what is an ox?

Just what is an ox?

The Hebrew word used in the Talmud is shor - (שור, rhymes with shore). Consider the following verse from Leviticus 22:27:

שור או כשב או עז כי יולד והיה שבעת ימים תחת אמו

Here are some of the ways it is translated into English:

When a bull or a goat is born, it shall be seven days under its mother... (Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses. [Alter seems to have forgotten to translate the word כשב]).

When an ox or a sheep or a goat is born, it shall be seven days under its mother...(S.R. Hirsch. The Pentateuch, translated into English by Isaac Levy.)

When any of the herd, or a sheep, or a goat is brought forth, then it shall be seven days under its dam..(The Pentateuch, translated into English by M. Rosenbaum and A.M. Silberman.)

When an ox or a sheep or a goat is born, it shall stay seven days with its mother...(The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. N. Sarna.)

When a bullock or a sheep or a goat is brought forth, then it shall be seven days under its dam...(Koren Jerusalem Bible.)

When a calf, a lamb or a goat is born, it is to remain with its mother for seven days...(New International Version.)

When a bullock, or a sheep, or a goat, is brought forth, then it shall be seven days under the dam...(King James Bible)

There are more, but you get the point. The word shor (שור) has been translated as a bull, an ox, a calf, a bullock and as a collective, any of the herd. The Koren Talmud and the Soncino Talmud translate it as ox. The ArtScroll Schottenstein Talmud as a bull. Confused? Me too.

Here are some of The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary definitions of an ox:

1. The domestic bovine quadruped (sexually dist. as bull and cow); in common use, applied to the male castrated and used for draught purposes, or reared to serve as food.

2. Zool. Any beast of the bovine family of ruminants, including the domestic European species, the 'wild oxen' preserved in certain parks in Britain, the buffalo, bison, gaur, yak, musk-ox, etc.

In his late nineteenth century translation of the Jerusalem Talmud into French, Moise Schwab translated the word shor as "le bouef" (rather than "le teureau"). De Sola's English translation of the Mishnah, published in 1843, uses the word ox. So does the 1878 compendium by Joseph Barclay, and the first complete English translation of the Talmud, by Michael Rodkinson, published between 1896 and 1903. The translation of shor as ox is goes back to these early translations, but the suggestion that the meaning of the word is a 'castrated male bovine quadraped' is certainly wrong. Jews are forbidden to castrate their animals, and a castrated bull would have been ineligible to use as a sacrifice. And so we must conclude that the best translation of the word shor (שור) is a bull (well done, ArtScroll!).

The delightfully named lecturer Dr. Goodfriend from California State University recently published a lengthy paper (in this book) on the various terms for cattle in the Bible, and the question of whether a castrated bull (a gelding) could have been offered as a sacrifice in the Temple. The good professor Goodfriend concludes that indeed the prohibition against the castration of animals "would have placed the Israelite farmer at a disadvantage as fewer suitable animals would have been available for his use." One possible way to overcome come this (other than to use cows for ploughing) would have been to import castrated bulls from those who lived outside of Israel.

And having sorted that out, let’s turn to the fun topic of the day. Injuries from cows.

“Cow-related trauma is a common among farming communities and is a potentially serious mechanism of injury that appears to be under-reported in a hospital context. Bovine-related head-butt and trampling injuries should be considered akin to high-velocity trauma.”

Injuries from Domestic bulls (and Cows too)

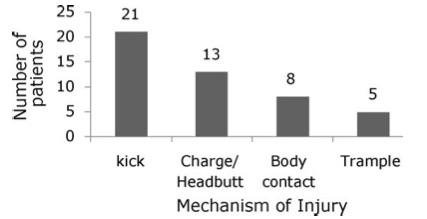

Mechanisms of injury from cows. From Murphy, CG. McGuire, CM. O’Malley, N. Harrington P. Cow-related trauma: A 10-year review of injuries admitted to a single institution. Injury 2010. 41: 548–550.

Much of the fourth chapter of the Talmud in Bava Kamma addresses injuries from domestic bulls and cows. In Masechet Berachot Rabbi Yitzchak reminded the devout not to get too lost in their prayers if there are cows (or bull or oxen) in the vicinity. It turns out that they cause all kinds of injuries even today. In 2009, orthopedists from Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital in Ireland published a fascinating paper entitled Cow-related trauma: A 10-year review of injuries admitted to a single institution. Over a decade, the hospital admitted 47 people with cow related trauma, most of whom sustained their injuries from kicking (unlike matadors, who suffer from horn related injuries). And next time you feel like walking across a field containing some gentle-looking cows, remember this: one of the patients was admitted with a head injury, a hip fracture and hypothermia after being trampled on by his herd of cattle in a field and found a number of hours later. (There are no details as to whether the injury occurred during shacharit or mincha).

“If a bull be a goring bull and it is shown that he is a gorer, and he does not bind his horns, or fasten the bull, and the bull gores a free-born man and kills him, the owner shall pay one-half a mina in money. If he kills a man’s slave, he shall pay one-third of a mina.””

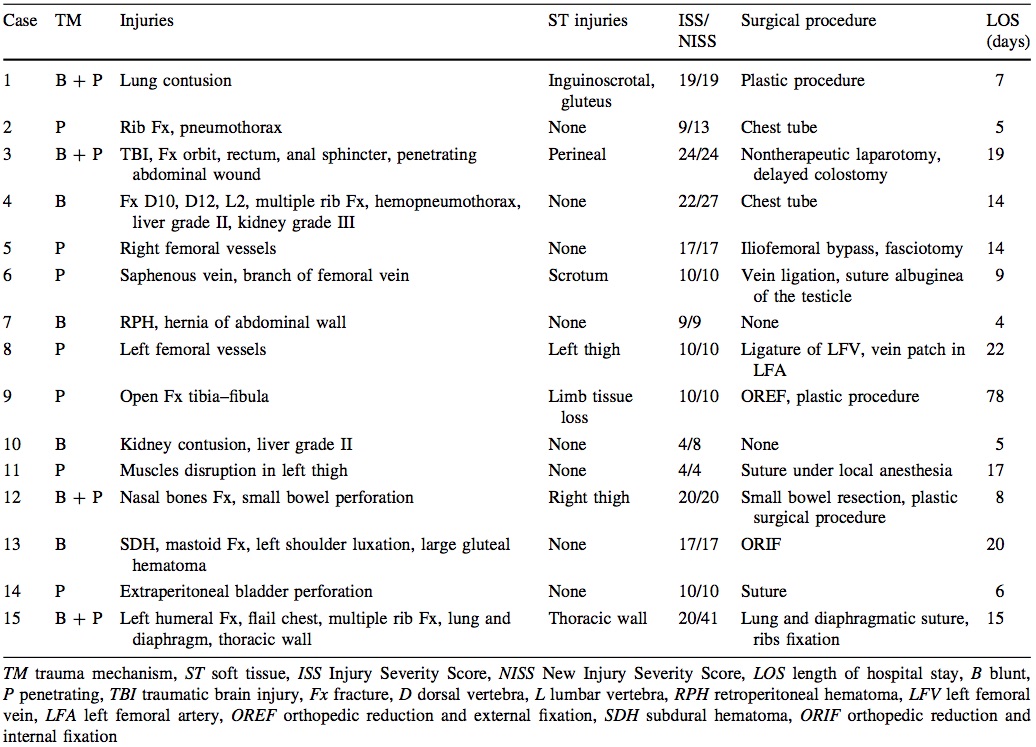

In another paper - Blunt Bovine and Equine Trauma - from La Crosse Lutheran Hospital in Wisconsin, researchers provided this illustrative case:

A 57-year-old male was pinned to the ground by a 2,000 pound dairy bull and repeatedly knocked to the ground forcefully at least seven times before he was able to crawl from the pen…Examination revealed the following injuries: bilateral flail chest, 13 rib fractures, bilateral hemopneumothoraces, renal contusion, two forearm fractures, left shoulder dislocation, bilateral scapula fractures, and dental alveolar fractures. The patient was treated by...mechanical ventilation for 15 days…His hospital course was complicated by Klebsiella pneumonia and at 16-month followup he remained severely dyspneic, unable to perform his usual farm work.

Finally, we should note a report published a few months ago in The Times (of London) about Scottish farmer Derek Roan, who was killed by one of his cows. Roan, whose family had farmed in the area for some 125 years, born on the farm had also appeared in a BBC documentary series This Farming Life.

Sheriff Joanna McDonald, who conducted a fatal accident inquiry, wrote that Mr Roan had died

… from extensive thoracic injuries as a result of an accident involving a cow whilst working on the farm. His death is certified in the post-mortem report as having been primarily the result of severe chest trauma.

Mr Roan intended to move a cow and its calf to join the main herd. The cow, a black Galloway beef cow weighing around 550kg, along with her calf, had been separated from the main herd a few days earlier due to suckling issues with the calf, who was approximately a week old at the time of the accident.

The farm vet, Dr Graham Bell, stated that it was good husbandry to deal with this issue in the way that Mr Roan had, to ensure that the calf was managing. The cow, who was aged around ten to 12 years, had never shown any signs of aggression before.

Cattle look gentle, and for the most part, they are. But they are large beasts with incredible strength. Hikers, (and farmers) beware. Please pray safely.